Who parented modern art? Is there a single artist whose work we can look at and say: "That's where modernism starts"?

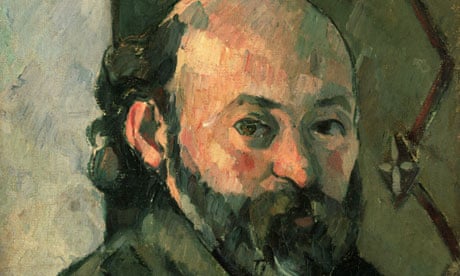

Some might nominate Manet, drawing crowds right now at the Royal Academy, for that historic role. There's no doubt that Manet's realism had incendiary effects on 19th-century French art. Yet years of looking at his paintings – searching for the reason he is seen as so much more radical than, say, Monet – have left me unconvinced. Instead, the artist who strikes me as the true father of modern art is a painter who began by emulating Manet then struck out in his own deeply subversive direction: Paul Cézanne.

The other day, I was looking at a video installation by American artist Cory Arcangel in Tate Modern. Colors consists of narrow bands of colour sliding across a screen while (at least in the bit I experienced) fragments of pop pulse on the soundtrack. It is actually a massively slowed down version of the Dennis Hopper-directed feature film Colors. Arcangel has done something archetypally modernist to this raw material: analysed it, picked it apart, until he reveals a strange, abstract beauty deep in the heart of things.

Cézanne was doing the same thing more than a century ago. I look at his paintings and see the seeds of everything artists have attempted since – right up to Arcangel's Colors. Consider Cézanne's painting Hillside in Provence, painted between 1890 and 1892, which hangs in London's National Gallery. A (very) rapid glance might tell you this is a tranquil picture of the Provençal countryside.

Look again. It is rather an incredibly charged and overwrought personal struggle with the view in front of Cézanne's eyes. Every dab of colour seems to be the result of days of thought and internal argument. Is this what is there? Is it like that? And what lies beyond what can be seen? By the time he has won his battle with the landscape, Cézanne has turned it inside out. We are looking at the geological structures of nature laid bare in the hot sun. Look closer still. Nothing is certain. In the distance, green-and-olive fields become squares and rectangles of green and olive, painted as the heat haze has simplified them in his eyes, transformed into abstract visual notations.

The modernist passion to look deeper, including deeper within oneself – to record not a simplistic picture of the world but a complex and hesitant perception of it – starts in the paintings of Cézanne. The abstract lines to which Arcangel can reduce a police thriller are born in that same fractured vision.

Looking at Cézanne's remade and fragmented visual world, I want to call his isolated colours "pixels". Anachronistic as it is, this word from the video age somehow seems accurate. Cézanne directly inspired Picasso and Braque in their Cubist experiments. But echoes of his revolutionary art reach further than that, from abstract painting to the strips of colour that float in Arcangel's art of the future.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion