Bill Viola/Michelangelo is subtitled Life Death Rebirth. The three words are the first thing you see in the Royal Academy’s pairing of the two artists. You enter fully alive. About half way through the dark, labyrinthine galleries, we meet an naked elderly couple, each projected on a slab of black granite, examining their own bodies with small torches. Apparently, he is searching for immortality, she for eternity. By now I wish it were over. At the end, we come across a woman silhouetted against a wall of flame. This is the last frontier.

The pairing of Viola’s video installations with Michelangelo drawings is not, the RA insists, an attempt to elevate the American video artist to the status of a modern Michelangelo. Rather, it is an attempt to point out affinities in subject matter and spiritual aspirations: “The nature of being, the transience of life, and the search for a greater meaning beyond mortality.” I can’t be doing with this sort of talk. Not here, not now, not, perhaps, ever.

There is no escape from the heavy breathing. My distaste for much of Viola’s later art (especially from the 1990s onwards) may well be connected to my own atheistic, let alone aesthetic inclinations, but why is it that I feel no such qualms in the face of Michelangelo, or most other religious art of the past, while so much of Viola’s work sticks in my throat?

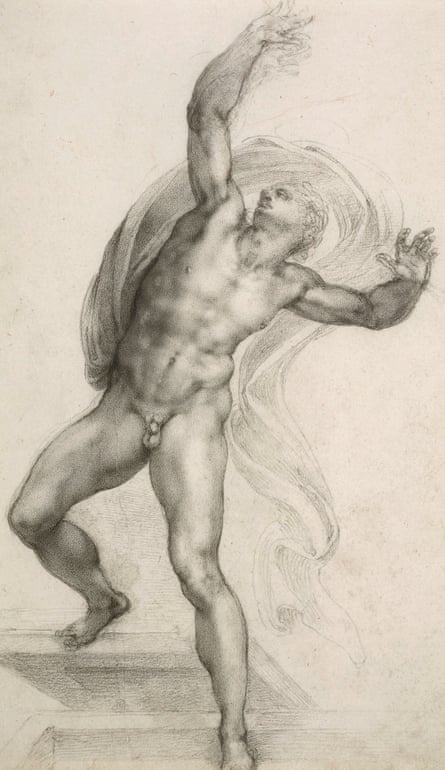

Gallery wall panels talk about Viola’s “deep preoccupations with the nature of the human soul”, and the “purity and intensity” of his engagement with the spiritual. Michelangelo’s paintings and sculpture are also described as “awe-inspiring in their grandeur”. Enough of this, already. But there is plenty more in the same vein. The wall caption to one Michelanglo drawing, The Risen Christ from 1532-33, talks about Christ’s “almost polished torso” reflecting “the radiant light with a glory that transcends materiality”. This is hyperbole. It is a small drawing in black chalk on paper, and does nothing of the sort. Nevertheless, Michelangelo’s drawings are full of life and fantasy and humour and eroticism and wit and violences, and have a breadth and depth Viola’s work never even approaches. Mostly borrowed from the Royal Collection Trust, and with the inclusion of the Royal Academy’s own Michelangelo Taddei Tondo marble relief, the Michelangelos are well worth looking at on their own account, preferably unaccompanied by these big, theatrical video presentations.

The best work of Viola’s here, the 1992 Nantes Triptych, shows a young woman’s stoicism, vulnerability and pain in the process of giving birth, as she sits, cradled at the end of a bed in the arms of a man. We hear her breathing and her cries. On the right hand panel an old woman (Viola’s mother) lies in a hospital bed. She is dying in a bleak, functional room. This is the only work here where reality really signifies: the pregnant woman’s cries and sighs, the rhythmic gurgle and hiss of the respirator attached to the old woman, the familiar light in the rooms, the business of being born and dying, the sense that we are attending events that are not staged.

The central panel shows a man underwater, more and less distinctly, and “suspended between birth and death”, according to Viola’s own catalogue commentary. This middle panel adds nothing, but only serves to separate the scenes to either side, which have the solemnity and squalor of fact. That’s where the real is here, and the only moment or scene in Viola’s 12 video installations that elicits any sort of affective response from me at all. The rest is all theatre and spectacle.

In installation after installation, Viola’s protagonists sink, rise and plunge through water. Some appear to sleep, untroubled and fully clothed in streams, without ever taking a breath. Others get trapped in their anguished reflections and burst from high-definition and dramatically lit watery wastes.

The camera loves the suspended, slow-mo droplets, the sluicing downpours and sudden eruptive splashes, the rocking surfaces, the bubbles winking on the water, but it all becomes very repetitive, and all the technical sophistication looks very hokey after you’ve spent some time with it. Often talked about as a video art pioneer, Viola suffers from his own seduction with his medium.

Michelangelo’s drawings are so vital and lively in comparison, so quick, with their writhing horses, herculean labours, their torments, their cheeky putti, the crucifixions and lamentations. Michelangelo is always engaging, on the level of drawing as much as subject matter. Drawing cheats time. Viola’s art is so much of its own time that it is already dated, dead in the water.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion