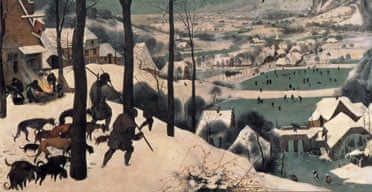

The mountains are the clue to the hidden meaning of Pieter Bruegel the Elder's masterpiece Hunters in the Snow. Flinty precipices rise up beyond the frosted valley, with its church and houses muffled in white, and children wrapped up like little balls, skating on frozen ponds. Mountains like this are not that common in the Low Countries. Why did the Flemish master make them such a prominent part of the greatest Christmas card scene ever painted?

Snow scenes are one of the delights of European painting, and at Christmas they're everywhere. Yet these homely pictures have a troubling pertinence: their true subject is climate change. Bruegel invented the snow scene, a unique achievement. All the other genres of painting - still life, portraiture, battles and histories, landscape - originate in antiquity. Depictions of snow originate with one man, and one terrible winter.

The year 1565 saw the coldest winter anyone could remember. The world turned white, birds froze, fruit trees died, the old and young faded away. It was a shock - and a foreboding. This seemed to be more than just a cold winter. The climate was perceptibly changing, and that is what Bruegel's snow scenes eerily record. All of them - from Hunters in the Snow painted in 1565, to Census in Bethlehem in 1566, to The Adoration of the Magi in 1567 - were made in response to that year and what it presaged. The key to their prophetic quality is right there in the mountains in Hunters in the Snow.

Those mountains are Alps. In 1552, Bruegel crossed the Alps on an artistic pilgrimage from his native Netherlands to Italy. His experience of western Europe's highest and coldest mountain range, which he recorded at the time in drawings that survive, stayed with him all his life, sharpening his mind's landscape, yet never as tellingly as in Hunters in the Snow. Here he seems to say that all the world is turning Alpine - in a new Ice Age.

He's right. Once, when the first painters made their marks on cave walls, all Europe was crushed and churned by glaciers that only survive now in the high Alps. In the 1500s and 1600s, these European glaciers were on the move, swallowing up pastures and devastating communities. The villagers of Chamonix, as the historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie discovered, petitioned their lords to do something about climate change: "We are terrified of the glaciers ... which are moving forward all the time and have just buried two of our villages and destroyed a third."

In Hunters in the Snow, the glaciers have reached the villages around Antwerp. Bruegel's prophecy is accurate. The climate was changing dramatically and dangerously, although in the opposite direction from today's impending crisis. The world was getting colder. Temperatures dropped globally in the Renaissance, so severely that climatologists call the era from 1400 to 1850 the Little Ice Age. The winter of 1565 was one of the first when everyone could see something had changed. But what was to be done?

This was a pre-industrial society that had only the most limited control over its environment. The Little Ice Age was a naturally caused phenomenon, and humanity - puny then in the face of nature - could only try to adapt. Bruegel's paintings are not just prophecies. They are recipes of adaptation, illustrating new ways to live with the cold: how to inhabit it, even enjoy it. Ice and snow turn the world upside-down. In Bruegel's paintings, the very chill that threatens life provokes vitality. People don't just shiver in the snow. In his Census at Bethlehem, while adults huddle miserably, children skate and sledge on the ice, as they do in Hunters.

Dutch artists took up Bruegel's new snow scene genre as winters deepened and hardened and the frosts that seemed novel in 1565 became routine (though still magical). In making everything look new and alien - stopping school and work, severing the chains of rural habit - snow created a wonderland that is celebrated, for example, in the paintings of Hendrick Avercamp, where entire Dutch towns are shown out on the ice while old people sit watching, wrapped up warm.

In Britain, the 17th-century English diarist John Evelyn recorded that when the Thames froze over, from December 1683 to February 1684, people treated it as a "carnival of winter". A carnival was a mad collective escape from drudgery, and in Abraham Hondius's painting, A Frost on the Thames, you can see what Evelyn means. Long-haired dandies glide across the solid river, visiting booths and tents, while cannons fire to salute a royal visit and children play ball games.

Yet, Evelyn points out, this midwinter celebration skated over the chilling facts: the poor were perishing from cold and hunger, the next year's harvest was dead in the ground, and trees were dying. It was a catastrophe. Somehow, the Thames "frost fairs" turned it all into a joyous Bruegelian celebration of life.

The last frost fair on the Thames was in 1814, when Regency fops were just as keen to get on the ice to flirt, as a cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson, of skaters on the Serpentine, shows. But in the 19th century, the communal hilarity Bruegel bequeathed gives way to a terrible solitude. Snow is no longer made homely by winter sports and braziers. It becomes the white shroud of death. Caspar David Friedrich's painting The Watzmann imagines a snowbound Alp, seen across green foothills, as a smooth, inhuman spectre remote from the fleshy concerns of the everyday. It is extreme, it is desired, and it will kill you. The Alps in Friedrich's day were still a menace to the economic and political life of Europe. The Little Ice Age still had the continent in its grip - crossing from France to Italy was terrifying. JMW Turner made the trip several times and glaciers and blizzards swirl in his paintings, most fantastically in his traumatic vortex of a painting, Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps.

By the middle of the 19th century, it was over. London would not see another frost fair. Today, to see people larking about on a frozen river in the heart of a great city, you have to go to St Petersburg. What changed? The industrial revolution had an impact on the climate as long ago as the 1850s, together with massive forest clearances in the US. A tendency for the world to become colder, which had been noticeable since the middle ages, was reversed by the stirrings of modernity.

Ice started to roll back from the world - but not from art. It is arguable that abstract art begins with all those snow scenes of the Old Masters, from Bruegel to Turner. When you look at fallen snow, the erasure of detail, the disappearance of perspective is what makes it so magical. Bruegel captures this: in his Adoration of the Magi, the action is partly obscured by falling snowflakes. He recognises the disengaging visual quality of snow, an insight that has surprising consequences. It would be fascinating to hang Hunters in the Snow next to a painting by the 20th-century Dutch visionary Piet Mondrian. The white emptiness of Mondrian's space, the pulses and chunks of colour animating it, uncannily (and not, I think, accidentally) resemble the patterns of white nothingness and human warmth in Bruegel's art.

The ghosts of the Hunters and the skating butterball children can be glimpsed in some of modern art's most haunting encounters with whiteness - in Jasper Johns' White Flag, in Robert Ryman's white monochromes, right through to the feathery snow in Peter Doig's paintings of winter sports.

Ice and snow are on the retreat now. This year is Britain's warmest on record. You've seen the news. Christmas card scenes suddenly look different when the north pole is vanishing. Can art respond to this, can it help resist climate change? The best work I've seen about global warming is Rachel Whiteread's installation of crumbling white plastic mountains in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall, created after she visited the Arctic. This homage to icebergs - at once colossal and disintegrating, its very material speaking of human destructiveness - conveyed the incomprehensible scale and dismal entropy of meltdown.

In modern cities, icy conditions are easily recreated by technology. Synthesised ice rinks have spread from Manhattan's Rockefeller Centre to parks and museum terraces everywhere. Maybe this is what winter will become: a refrigerated carnival, an attempt to recreate artificially the cherished memories and folk tales of winters lost for ever. In Tarkovsky's film Solaris, a space station orbiting a distant planet has a print of Bruegel's Hunters in the Snow in its lounge. It is the astronauts' memento of Earth. It's a chilling thought that, for future generations on a radically altered Earth, Hunters in the Snow may fulfil just this purpose: preserving the idea, at least, of what a snowbound planet looked like, how human it was, how paradoxically warm and fun.

Bruegel captured humanity's double relationship with winter: we fear it and we love it. Surviving winter is part of what makes us human. For Whiteread as for Bruegel, whiteness is wondrous, frightening - and the world would be a poorer place without it.

· Private Life of a Masterpiece: Bruegel's Census at Bethlehem is on BBC2 at 6.10pm on Christmas Day.