Simunye, We Are One: Tales from Soweto, South Africa

When I told a customs security guard in Johannesburg,

When I told a customs security guard in Johannesburg,

South Africa that I would be spending six weeks in Soweto - a township southwest of Johannesburg - he appeared shocked and asked me, “You know that’s a ghetto, right?”

Over the past two summers, I have traveled to Soweto on an immersion trip through my former high school, Bellarmine College Preparatory. While these trips gave me contact with the gritty reality of Soweto as it struggles to recover from the residual effects of the apartheid regime, I realized that true solidarity is fostered through developing relationships with those who live on the margins in a “ghetto” that appears foreign within its own country.

After sharing his family’s struggles throughout the apartheid regime during a previous trip, my friend Roy told me, “I didn’t think guys like you actually cared.” As Roy taught me, the “us” of humanity often gets fragmented by race, borders, and socioeconomic divides. People like Roy made me realize that while coming into contact with Soweto through a school trip was necessary, it is not enough. As a result, after having finished my first year at Georgetown, I have decided to return to Soweto once more with my good friend Drew Descourouez – a student at Santa Clara University and graduate of Bellarmine – but this time, we have a different focus. During our two-month stay in Soweto, we will be working on a project with the Ignatian Solidarity Network (ISN), an organization that advocates and educates themes of social justice based on Jesuit values, to publish the stories of the people of Soweto because for us, storytelling is relationship building. Our project is called The Simunye Project because the Zulu word “simunye” translates to “we are one.” This is the theme of our project: telling a shared human narrative in hope that if we begin to tell our story as one, we might start living as if we all shared our humanity.

As I take my first step back onto the ashy South African soil, the tangy smell of smoke welcomes me back to Soweto. A cloud of smog looms over the city, creating an endless atmosphere of gray. Exotic stares of confusion scream, “You’re not from here.” This is Soweto, my other kasi – my other home.

While Soweto’s history as a township has left many of its residents in deprived socioeconomic states, its rich culture and thriving community make it wealthy at heart. In the midst of unemployment hovering around 50 percent, the streets are filled with soccer games, sawubonas (hellos), and special handshakes that serve as a township greeting. Soweto was at one point home to many of South Africa’s heroes, from Nelson Mandela to Desmond Tutu, yet current corruption and political uprising continues to leave Soweto as an isolated black-eye southwest of Johannesburg. Soweto comes as a stark contrast to the skyline of Johannesburg, which is the financial capital of South Africa and thus the richest city in South Africa. Because of this, South Africa has a Gini Coefficient of 63.4%, meaning that it is one of the most unequal countries in the world by measure of income.

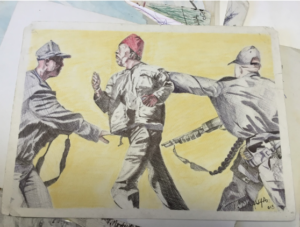

In the midst of a township that is easily despised and readily disposed, many of my own personal heroes continue to demonstrate courage against corruption in same streets that Mandela once walked. Whether it is Ms. Tshabalala turning her house into The Nkanyezi Centre, the first stimulation centre for children with autism and cerebral palsy in Soweto or Tshegofatso telling the story of his family’s experiences under apartheid through art, I am honored to work on a project to share the stories of those not often heard but who are screaming to write a new chapter in Soweto’s narrative. Within the first two days of arriving in Soweto, I met Monde, a local gardener who helps feed and fund The Nkanyezi Center. After speaking with Monde, he told me how, after losing a manufacturing job he did not enjoy, he turned to alcohol to suppress his lingering depression. Eventually, he began to pursue his passion, gardening, at home, and after a friend noticed his devout work, The Nkanyezi Centre offered him a job. Now, instead of weeding off addiction, he plants seeds of nourishment for children that he considers his own.

As author T.H. White notes in his famous novel, The Once and Future King, “The business of the philosopher was to make ideas available, and not to impose them on people.” As much as I believe in being a strong advocate going into Soweto, I believe that the true storytelling will be derived from my interactions and intersections with the people of Soweto, whether it is Kele showing me how he uses music to deal with the residual effects of apartheid or Dumisani explaining the importance of remembrance in the midst of forgiveness as a response to the Hector Pieterson shootings of 1976. As a result, I hope to learn the philosophy of the people of Soweto as they strive to create a better South Africa in a post-apartheid, post-Mandela world. As White notes, I hope to share this philosophy to larger audiences, and while I know that I cannot enforce that philosophy, my greatest hope is that we begin to listen to the voices of those on the margins in order to address these challenges that face our world “as one.” To me, Soweto is not a place that needs to be solved but rather a place that needs to be heard.

So, as I begin my journey in Soweto, I am excited to learn more about the use of storytelling in combating the systemic cycles of poverty. To me, Soweto is not a ghetto. It is not a place that people should be discouraged from entering with such strong negativity. It is my second home. It is a place I want to be. It is a place to which I am excited to return and a place I am excited to share.