Why Is Hollywood Developing Three Different Joker Movies?

The flurry of news about multiple films featuring Batman’s chief villain shows just how desperate the industry is becoming.

No subgenre has seen a more massive boost in prestige in Hollywood than the comic-book film. It used to be surprising when critically acclaimed young directors like Bryan Singer would take on a project like X-Men, whereas now it’s practically a matter of course for fledgling artists to leap at such an opportunity, and for Oscar-feted stars to burnish their credentials with a superhero jaunt (think Benedict Cumberbatch in Doctor Strange or Cate Blanchett in the upcoming Thor: Ragnarok). But at last, we have an example of this trend running in the opposite direction, of a bulletproof comic-book brand that’s losing much of its luster: the Joker.

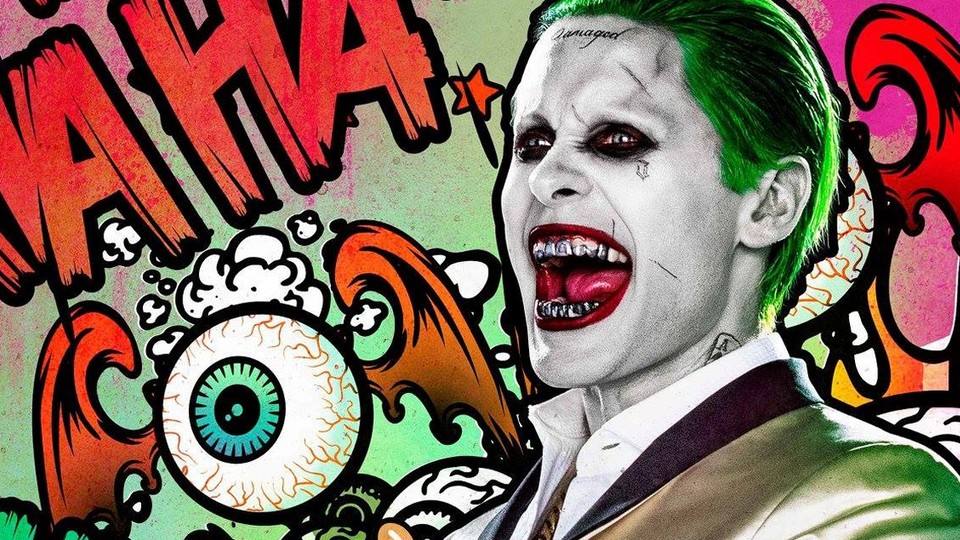

When Tim Burton made his first Batman film in 1989, he cast one of Hollywood’s biggest and most dependable stars in the role of Batman’s greatest enemy. Jack Nicholson, already a two-time Academy Award winner (he’d later collect a third trophy in the 1990s), was paid a king’s ransom for the role (his cut of the film’s profits ran to an estimated $50 million) and received top billing above the movie’s ostensible lead Michael Keaton. Since then, the Joker has remained the most prestigious comic-book movie role, winning Heath Ledger a posthumous Oscar for 2008’s The Dark Knight; Jared Leto was cast in the role in Suicide Squad not long after his Oscar win for Dallas Buyers Club.

Now, it seems, Warner Bros. (who produced all of these Joker films) is desperate to rediscover the cachet that has vanished from the role. Over the last few weeks, widespread industry reports have suggested the studio is simultaneously pursing three Joker projects: a Suicide Squad sequel, a standalone film focusing on the villain’s relationship with his partner in crime Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie), and, mostly bizarrely, a Joker “origin film,” to be directed by Todd Phillips (The Hangover) and produced by Martin Scorsese. Leto would ostensibly star in the first two projects, but for the third, Warners reportedly has a bigger target in mind: Leonardo DiCaprio, who recently won his first Oscar.

DiCaprio is, of course, a longtime collaborator of Scorsese’s (they’ve made five films together), as well as an actor who has branched out into more villainous, challenging roles (as in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained). But according to The Hollywood Reporter, the chances of landing DiCaprio “could be slim to none,” despite Scorsese’s involvement; the very idea of his casting was met with online mockery from many a film publication, along with reports of Leto furiously making his displeasure known to the studio. In 1989, the notion of a Batman movie was risky, but Burton still got Nicholson on board. What’s changed since then? Simply put, studios’ obsession with making franchise films and audiences’ growing backlash against that oversaturation.

The poor critical reception to Leto’s performance in Suicide Squad didn’t help, of course. But even though that film was lambasted, it made serious money, grossing $745 million worldwide, enough to encourage Warner Bros. to greenlight a sequel and the Joker/Harley Quinn spinoff (which will be written and directed by Glenn Ficarra and John Requa of Crazy, Stupid, Love). The studio has invested heavily in its DC Comics franchise and saw major critical and commercial success this year with Wonder Woman. It has Justice League coming in November and films like Aquaman, Flashpoint, Green Lantern Corps, a Wonder Woman sequel, a standalone Batman, and many more on deck, along with the aforementioned Joker movies.

Despite Wonder Woman’s success, the studio’s approach seems to be throwing films at the wall and seeing what sticks, as it’s doing with the Joker projects. The idea, according to The Hollywood Reporter, would be to set up a franchise within a franchise—the Leto films would be part of the main connected universe, but the Scorsese-produced “origin” film could be disconnected and given different branding, to distinguish it and perhaps mollify Leto. Still, “Warners executives are acutely aware of the risks of audience confusion,” the story helpfully notes.

The prospect of multiple Joker films coming out in the new few years is maddening from both a creative and a business perspective. But it’s exactly the kind of moneymaking gamble studios are willing to take as they try to eke out new revenue streams from the same pieces of intellectual property. This summer was officially Hollywood’s lowest-grossing in 10 years ($3.8 billion), with the worst ticket sales in 25 years ($428 million). That’s because big weekends in 2017 were devoted to sequels to films audiences clearly hated (such as the fifth Transformers and the fifth Pirates of the Caribbean); vain attempts to launch entire franchises within one movie (Universal’s The Mummy); and weak cash-ins on ’90s nostalgia (Baywatch, Ghost in the Shell, Power Rangers).

It would be hard for studios to throttle back at this point. Creaky franchises like Transformers, the “monsterverse” (centered on creatures like King Kong and Godzilla), and the “Dark Universe” (revolving around Universal monsters like Dracula and The Mummy) have expensive writers rooms devoted to their continued existence. Studios hire award-winning screenwriters to work with producers and churn out scripts for spinoffs and sequels. It’s why a film centered on the Transformer Bumblebee is in production and why there were several announced sequels to The Mummy in the works before the film even hit theaters.

Hence, the Warner Bros. plan to make three Joker movies simultaneously. The studio seemingly doesn’t care about diluting the brand, a process that’s been slowly happening for decades anyway. The gap between live-action film portrayals of the Joker has narrowed dramatically: It was once 23 years (between Cesar Romero’s take in the 1966 Batman: The Movie and Nicholson). Then, it was 19 years (between Nicholson and Ledger), then eight years (between Ledger and Leto). Now, it could be as little as three. The desperation, with every cast change, is becoming more evident; no wonder Leo isn’t interested.