The art of deciphering handwriting is a valuable skill for any genealogist. This study of old writings and inscriptions is called paleography (or “palaeography” in the UK), and can take a lot of time and knowledge to perfect - though with some practice and our tips below you’ll greatly improve your skill set.

Early writing was not exactly standardized, and the style of handwriting often reflected a person’s social status and gender. Many different styles of writing, known as ‘hands’, were taught and with different methods through the years. Spelling also varied greatly, and many chose to spell phonetically as it sounded to them.

Let’s start with a few quirks of early handwriting you will probably come across during your research, including the leading “s” character, the use of name abbreviations, and the use of letter thorns.

The Leading “S” or Long “s”

Though usually referred to as a “long s” this character is sometimes called the “leading s” as usually appears as the first of two “s” letters (but not always), though it resembles a cursive letter “f” more (without the crossbar).

An example of the leading “s”, in which a double ‘S” looks like a modern ‘f” followed by an “s”. The name above is “Jesse”.

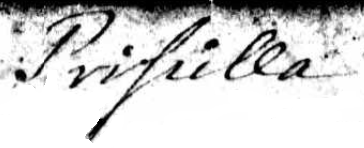

An example of the long s in the middle of the name “Priscilla”

In some cases, this long s would appear at the start of words or in place of a single letter s in the middle of words, though the grammar of it is somewhat confusing. It was not used as a capital letter, not before the letter f, and not at the end of a word, for example. It’s use dropped during the 18th century, and seems to have disappeared by the end of the 19th century in America (earlier in typed works).

Ticak, Marko. “A Short History of the Long S”. grammarly blog. 10 October 2016.

West, Andrew.“The Rules for Long S” BabelStone Blog, 12 June 2006.

Wikipedia, Long s

Name Abbreviations

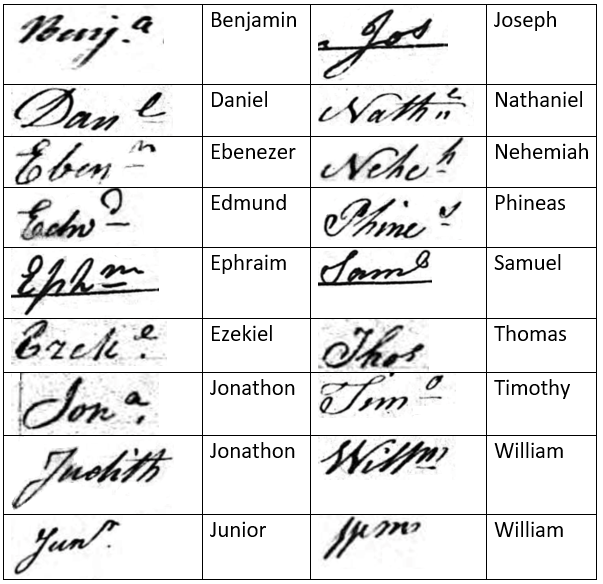

You’re likely to come across name abbreviations in your research, but you might be surprised to see some of them almost look like fractions or with interesting punctuation. Most though, are just shortened versions of the original name. Knowing what these might look like will help you when attempting to find your ancestor’s name among records.

Chart above showing examples of nicknames we found in various 1790 US Census records across New England.

The letter Thorn

You may see what looks like the letter “y” or word “ye” in place of the word “the” in some early texts. This was actually a letter called thorn, from early runic alphabets, and pronounced with a “th” in most cases. The word “ye” was actually pronounced as “the”.

The following example from the beginning of the 18th century, shows the long s at the start of the word “son”, and the ye thorn, shown subscript, in place of the word “the” in the date of births.

This text above has two similar lines, the first reading “his son born September ye 8th” and the second line reads “his son born April ye 5th” taken from Massachusetts Town and Vital Records, 1620 - 1988, under Barnstable, Town Records 1713 - 1781, Vol 2, page 175, provided by Ancestry.com.

In the example below, the letter y appears to be used in place of “and” which is not a case of the letter thorn, but something else entirely (perhaps an elaborated ampersand) you should be aware of during your research.

The above text reads “Son of William and Elizabeth” using Old English spelling, what looks like the use of a “y” letter, and name abbreviations.

Haven, Cynthia. “Eth, thorn, and ash: they flunked the screen test for our alphabet” Stanford University, The Book Haven. 27 August 2013

Oikofuge. ”Letters from Abroad: EDH and Thorn”. 17 October 2018. Oikofuge.com.

Wikipedia, Thorn (letter)

Now that you are familiar with a few of the unusual characteristics of early handwriting, let’s move on to tips for deciphering the writing you might come across in your work.

Compare the handwriting:

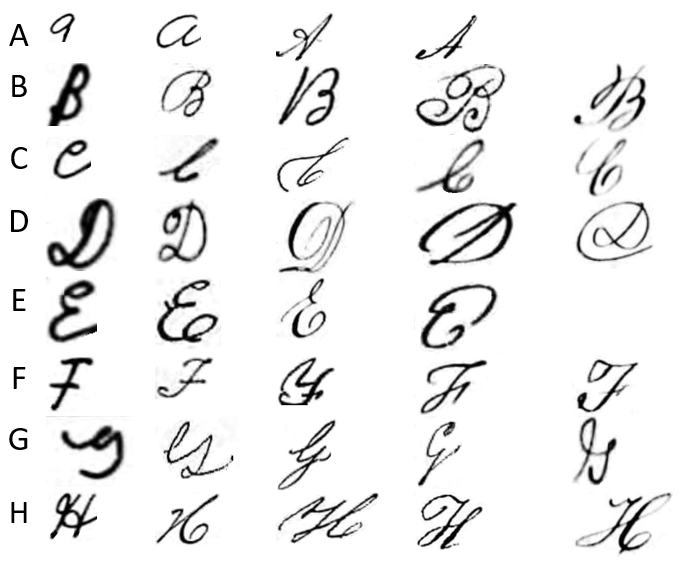

Look for a similar letter elsewhere on the same document to compare - do they match? Is that letter “S” really a “T”? It may be helpful to create your own alphabet chart using sample letters from the document.

Keep an eye out for letters that look similar and can be confused for each other (or even used interchangeably on purpose, as was often the case with i and j, or u and v)

Try to trace the letters and think about how you write - do the letters or words feel similar?

Find a copy of similar writing from the time. A quick google search for “19th century alphabet” will show you examples of script round-hand from the 1800’s as well as other styles. We sourced each of these letter samples in the images below from various census records in the early United States (click to expand).

Find another entry, if an a book of baptisms for example, that should have a few of the same words and may be easier to read. Also look up common phrases or terms in the type of document you are trying to decipher, that might help you guess words (this is also a key trick when translating documents).

Use your ears:

Read the text you are trying to decipher out loud, to the best of your ability.

Try saying the name you are looking for out loud, and how it might be spelled phonetically, Often census takers or customs officials would write down whatever they heard, dropping silent or double letters, confusing certain letters like “V” and “G”, and just guessing phonetic spellings.

Think if the person recording this document was listening to an immigrant, and how their name may sound with an accent.

Other tips

Can you change how the image looks with photo editing, like adjusting the contrast or brightness to make it easier to read? You could also enlarge it, or try zooming in.

If copying for your records, transcribe with original spelling and abbreviations then write a “modern translation” below it if necessary.

Reference dictionaries of the same time period, or research old occupation titles or archaic medical conditions.

Get a group consensus! Another pair of eyes might be all you need to see clearly. There are Facebook groups that exist for this purpose.

See also Abbreviations and Glossary