TikTok viral ‘henna freckles’ done by white creators are a problem, say South Asians

- Henna, a dye, traditionally applied to the hands and feet, has grown in popularity on sites like TikTok, where people are using it to create freckles

- South Asians say henna is only seen as ‘cool’ now because it’s used by white people. One says she used to be called names for the henna on her hands and feet

Henna is a plant-based dye that many cultures in different continents have used as a form of body art for millennia.

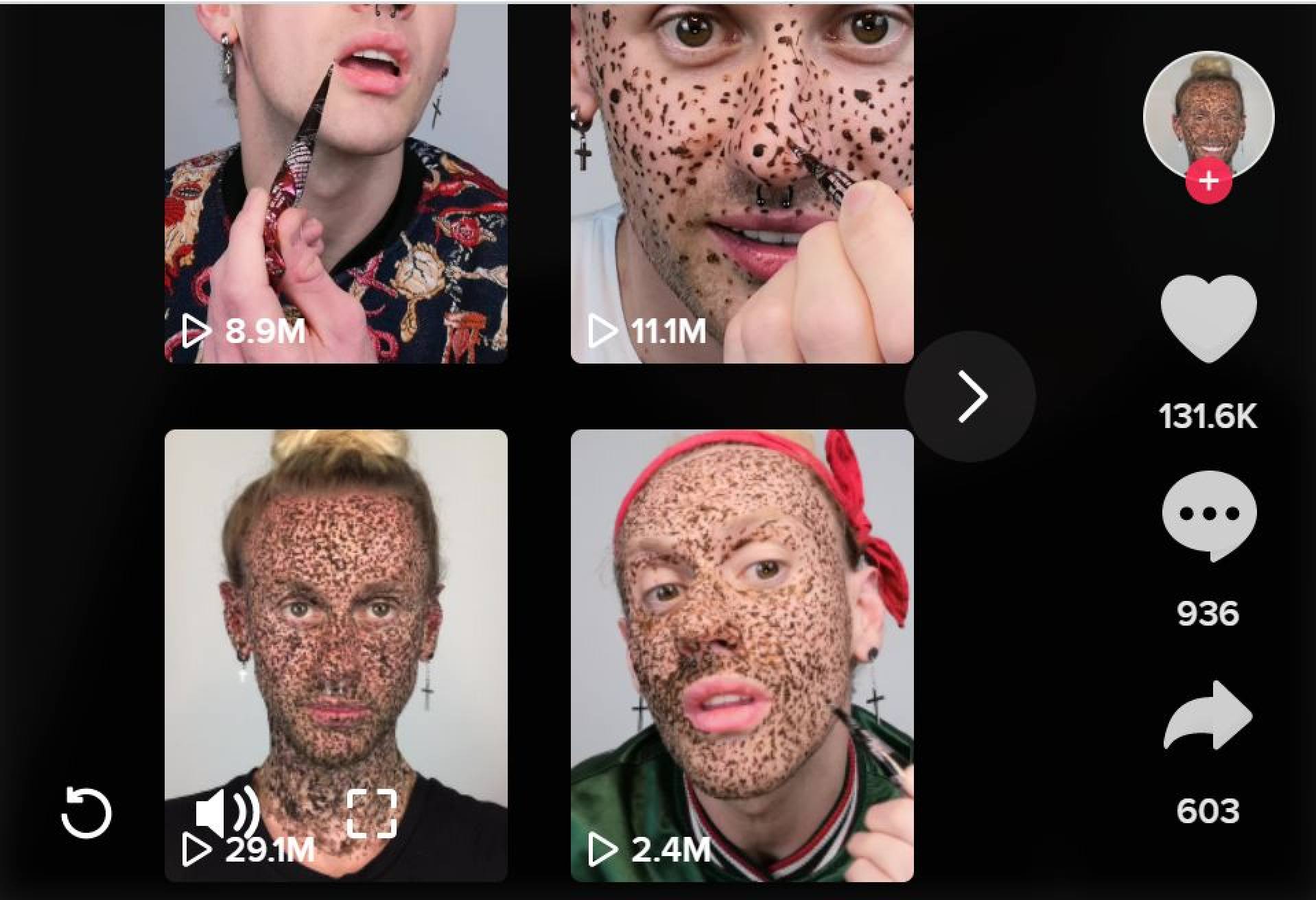

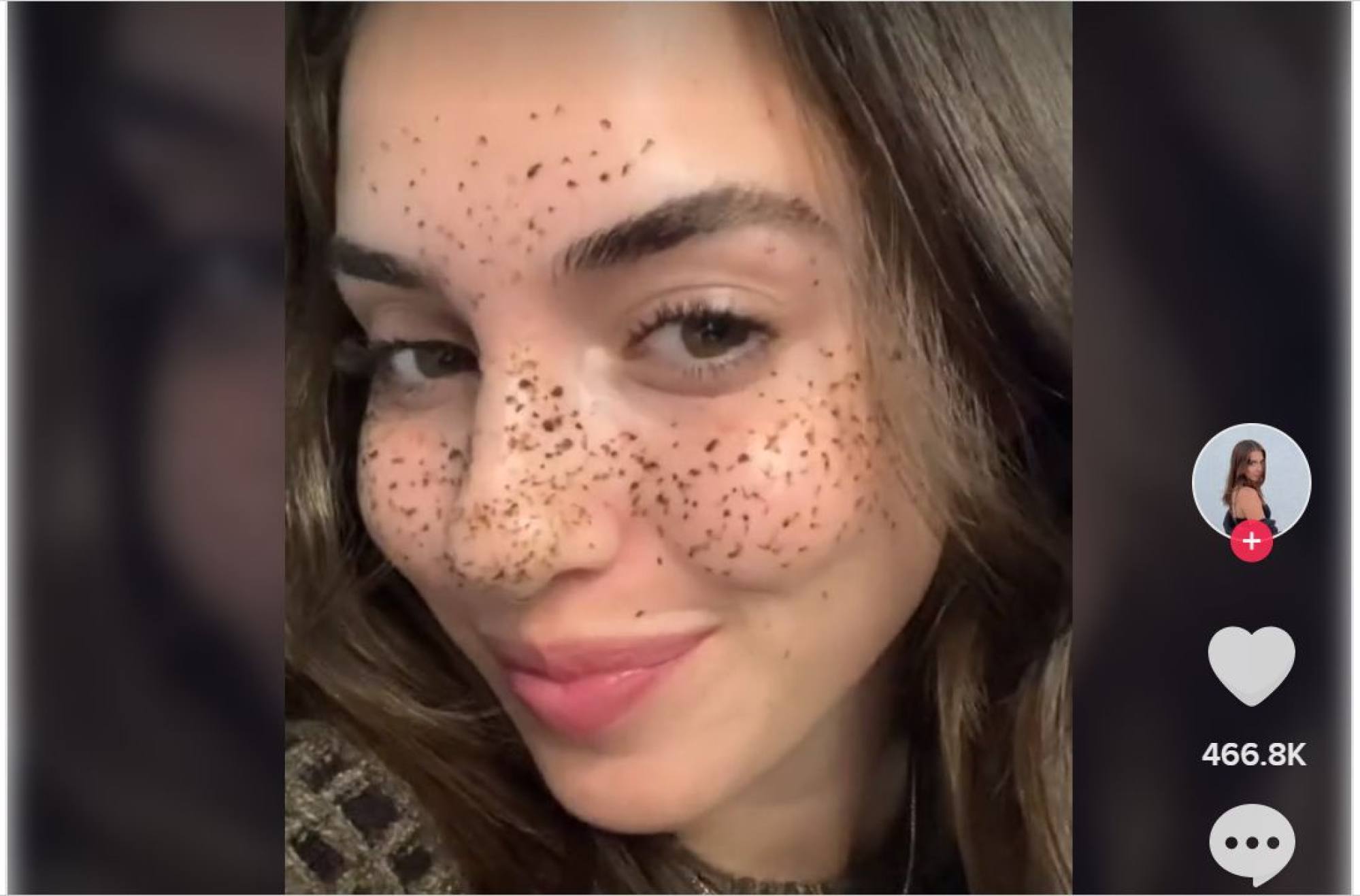

Over the past two years, a seemingly new use for henna has blown up on TikTok – users of the short-video social media platform are using it to draw semi-permanent freckles on their faces.

Some South Asian creators on the app have spoken out against the trend, calling it an act of cultural appropriation. While various Middle Eastern, Asian and African cultures use henna, creators belonging to these cultures argue the trend pushes white, Eurocentric beauty standards that misuse henna and ignore its cultural value.

More broadly, some South Asian creators and experts say the trend reinforces a structure of racism that has developed on social media, saying they feel ignored by apps that platform white creators who do not give credit for ideas for content or trends that people of colour originally introduced.

In January, a 20-year-old Australian-Indian student, Jasmine Diviney, said she saw a TikTok video, which has since been deleted, of “henna freckles” gone wrong, where the white creator warned her audience to do a patch test when trying the trend because her freckles ended up looking too large and she could not wipe them off.

The ‘fox eye challenge’: just a look, or an insult to Asians?

Diviney posted a response to the video and wrote a caption that read, “Indians have been telling y’all not to use henna like this since day one but I guess y’all wanna learn the hard way”.

She says that in India, where she lives, it’s “common knowledge” not to use henna on the face because of how sensitive the skin is.

Diviney’s TikTok has sparked a debate in the comments, where some viewers accused her of trying to claim ownership of henna and exclude others from using it.

“Indians are not just gatekeeping for the sake of gatekeeping,” says Diviney. “We are genuinely trying to help you by showing you how to use it in the appropriate way.”

Diviney described henna freckles as cultural appropriation, which is when someone uses or adopts a practice from a different culture, often without showing proper respect for that culture.

Where henna tattooing began: as an ancient wedding ritual

According to St. Thomas University in Canada, henna – known as mehndi in Hindi and Urdu – is traditionally applied to the hands and feet, normally at celebrations and weddings in South Asian communities. Middle Eastern and African cultures also use it to dye hair, nails and fabrics.

Lakshmi Nair, an 18-year-old Indian woman who was born in Canada, also spoke out against henna freckles on TikTok. She believes when people participate in trends that use henna “incorrectly”, it “discredits” the significance of her culture and the way the product is typically used.

Ome Khan, a 30-year-old Pakistani-American who also criticised henna freckles on TikTok, says that as a child, other kids would often mock her for wearing henna to school by calling her names like “poop hands” and “poop feet”.

She says that white creators who “just want freckles” are the ones mainly taking part in the trend, and this feels problematic to her because “I don’t know a lot of brown people who have freckles”.

Anyone can have freckles, but people with lighter skin are more likely than people with darker skin to have them. Khan feels the trend promotes Eurocentric beauty standards and prioritises freckles over more typical South Asian features.

Lawyer and anti-racism activist Kudrat Dutta Chaudhary says it is understandable that South Asian women feel this way about the trend, but also said it’s important to note that some people of colour, such as people from Latin American communities, have spoken out about being bullied for having freckles as children.

Khan and Nair, who both said they’ve been mocked for wearing henna, say the trend implies that South Asian culture is only “cool” when white creators show an interest in it. They pointed to yoga and chai as other examples of how their culture has been “whitewashed” and reduced to fads and trends.

Chaudhary says these comparisons are linked to a “colonial hangover”. She said the notion that white people were intellectually and culturally superior to people of colour – reinforced when India was a colony of the British Empire, before it gained its independence in 1947 and established its constitution in 1950 – persists today.

One consequence of this is that skin-whitening products, which are largely thought to promote Eurocentric beauty ideals, are still popular in India.

US beauty brands called out for burying hot products’ Asian roots

Sunaina Maira, a professor of Asian-American Studies at UC Davis in the US state of California, says that while cultures borrow from each other all the time, particularly in fashion, it’s still important to consider who is profiting from these trends.

“I think one has to challenge this debate and push it further by talking about things like who is making money from this, and who is getting left out, because those are the things that are harming people,” she said.

Lekha Nettem, a 20-year-old South Asian TikToker who decided to try henna freckles despite the controversy surrounding the trend, feels that as long as people buy their henna from women of colour, for example at their local Indian market, they “keep her culture alive” and “stay more connected to the root of the cultural practice”.

However, Davina Rajoopillai, a marketing and advertising expert who co-founded Badlands, a company focused on diversity in television and social media, said that even if trends like this boost sales for products like henna, South Asian businesses should gain credit and equity on top of the profit.

Like Maira, Rajoopillai said these trends point to broader issues of inequality in the beauty industry, because South Asian women have had to “work hard at being represented”. When white creators go viral for trends with South Asian products, it serves as a reminder of the “slow progress that has been made in recent years”, she said.