FICTION

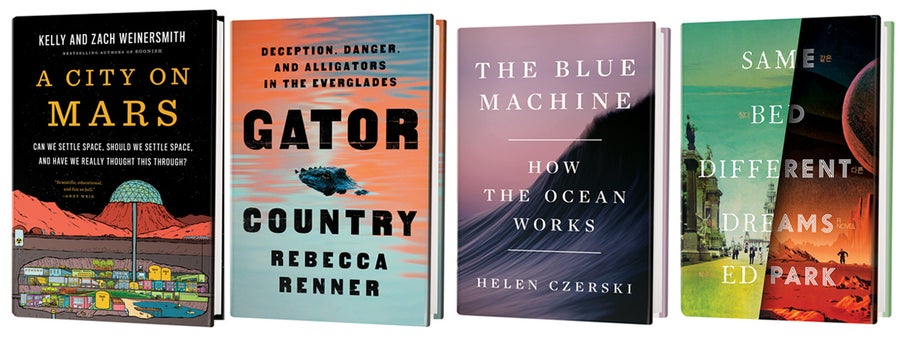

A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?

by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith

Penguin Press, 2023 ($32)

If the space race in the 1960s was solely about geopolitics, the latest rush off Earth is, at least at times, about something slightly more ineffable. By building a future in space, human society has a chance to reinvent itself, to forge something different—and maybe better. Right?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

For their latest book, the husband-and-wife team—Kelly Weinersmith is a biologist, and Zach Weinersmith is a cartoonist who draws the Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal comic—spent four years researching how humans are becoming space settlers. During that time, they began referring to themselves as “space bastards” because they found they were more pessimistic than almost anyone else in the spacefaring industry. The result is a breezy peek at the near-term future of humanity in space, and the upshot is that this future is as cold, dark and unfriendly as the cosmos itself. “Space: quite bad,” the Weinersmiths declare.

The authors write in a witty voice that still commands authority, like a middle school science teacher who celebrates Pi Day but most assuredly wants you to accurately calculate circumference. Many nonfiction books about space, especially the history and future of exploration, are suffused with an almost religious degree of optimism and zeal. The Weinersmiths are not optimistic, but their book remains approachable rather than overtly cynical. It helps that the chapters read like a conversation over drinks, where the writers are as comfortable discussing the ramifications of sex on Mars as they are expounding on the economies of coal towns in early 20th-century Appalachia.

Alongside the lighthearted tone, the illustrations on nearly every page lend a surprising amount of heft. Even when the cartoons can't fully explain the phenomena the authors are describing, the drawings are still delightfully useful. In one example, the Weinersmiths describe harmful cosmic radiation, contrasting DNA-damaging charged particles to the width of a human hair, which is about 50 microns across. The cartoon is labeled as “not even kind of sort of vaguely close to scale,” which manages to convey tininess that is inherently difficult to grasp.

As the Weinersmiths grapple with psychology; rotating space stations; inhospitable worlds; the truth about space diapers; and the inevitability of space politics and, perhaps, war, you can tell they are doing so only half-cheekily. “There's no political corruption on Mars, no war on the Moon,” they write in the opening lines. The subtext is that we're humans, so we'll probably get there. Or maybe, they say, we should consider the rarely discussed alternative: hanging out here, in the grass, by our home. —Rebecca Boyle

IN BRIEF

Gator Country: Deception, Danger, and Alligators in the Everglades

by Rebecca Renner

Flatiron Books, 2023 ($29.99)

Journalist Rebecca Renner returns to her home state of Florida determined to uncover the truth (if any) behind the exploits of a legendary Everglades alligator poacher. She also follows a reclusive wildlife officer's infiltration of a poaching operation. As Renner wades through the complex tangle of gator poaching's social, political and cultural roots, she stirs up the cloud of assumptions lurking within our attitudes toward nature and the proper stewardship of its resources. Filled with vivid descriptions of Florida's wild places and backcountry cultures, this well-paced account both celebrates and transcends its iconic swamps. —Dana Dunham

The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works

by Helen Czerski

W.W. Norton, 2023 ($32.50)

Learning, it's often said, begins with realizing how much you don't know. The Blue Machine proves this saying about the ocean, a behemoth that, superficially, may appear monolithic. Helen Czerski shows that forces such as temperature, gravity and salinity not only create an endlessly varied seascape but also shape life and conflict on Earth. Despite focusing on a terrestrial system, her descriptions of invisible physics and the deep sea frequently evoke the otherworldly. Like an early underwater explorer, a reader taking in the book's teachings will feel like “a land mammal cast fully into this alien world of seawater.” —Maddie Bender

Same Bed Different Dreams

by Ed Park

Random House, 2023 ($30)

Ed Park's acerbic commentary permeates what is three novels rolled into one. First, has-been Korean American writer Soon Sheen now works for GLOAT, which uses algorithms to extract every last iota of information from customers. Second, Sheen reads the magnum opus of a rising star Asian writer, Same Bed Different Dreams, which offers snippets of alternative history of the supersecret Korean Provisional Government, established in 1919 under Japanese occupation. Third, an African American sci-fi pulp writer composes a space opera about the end of the world set in 2333. Park's triumvirate taps into humanity's desire to rewrite history and into the chilling reach of technology. —Lorraine Savage