Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the epidemiology, microbiological features, as well as antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Nocardiafrom cases with ocular nocardial infections seen over a period of 8 years in a tertiary eye care hospital.

Methods

Microbiology records of 164 cases of culture-proven ocular nocardial infection diagnosed between March 1997 and February 2005 were reviewed retrospectively. The outcome data included isolation rate, predisposing factors, demography (age and sex), and category of infection, utility of conventional diagnostic methods, microbiological profile, and antibiogram–resistogram patterns.

Results

A total of 164 (3.1%) Nocardiaspecies were identified among 5378 culture-proven cases. Ninety-six (58.5%) isolates were from corneal scrapings followed by vitreous biopsy (17.0%). Most (58.0%) of the cases were between 51 and 80 age groups. Male preponderance was obvious. All the 164 (100%) nocardial infections were identified by culture. Of 125 ocular specimens subjected to Gram's staining, nocaridal filaments were identified in 70 (56%) specimens. In addition to KOH mounting, modified AFB staining was also found to be helpful. Upon in vitrosusceptibility testing, 98.7 and 90.2% of nocardial isolates showed sensitivity towards amikacin and ciprofloxacin, respectively.

Conclusions

Ocular nocardiosis is relatively rare among ocular infections. Amikacin and ciprofloxacin are highly effective in treating ocular nocardiasis. Prompt and accurate microbiological diagnosis and early administration of these antibiotics may have a positive effect on the ocular outcome as well as in controlling nocardial prevalence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Members of the genus Nocardia belong to the family Mycobacteriaceae and was first isolated by Edmond Nocard in the year 1888.1 They are aerobic, thin, filamentous, branching, Gram-positive bacteria found in fresh and marine water, soil, dust, and decaying vegetation. Nocardia species are ubiquitous in nature and not present as normal flora either in the eye or in the respiratory tract. Nocardiosis is usually an opportunistic infection caused by Nocardia species and reported as cutaneous, ocular, and pulmonary diseases in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.1, 2, 3, 4 Ocular nocardiosis is believed to be a rare entity compared to other forms. However, there are reports of nocardial infection of the ocular adnexa manifesting as persistent epithelial defect,5 conjunctivitis,6 dacryocystitis,7 scleritis,8 keratitis,9, 10, 11, 12, 13 episcleral granuloma,14 and endophthalmitis.4, 15

To start appropriate therapy, apart from clinical examination, precise laboratory diagnosis and the results of in vitro anti-bacterial susceptibility testing are important.9 The clinical diagnosis of ocular nocardiosis is difficult,2, 16 as the clinical picture resembles mycotic keratitis or keratitis caused by atypical mycobacteria, and the infection is missed often. Also, misdiagnosis is common, which delays ocular nocardiosis diagnosis where patients usually suffer from significant ocular morbidity for a prolonged period and patients are subjected to injudicious usage of topical corticosteroids. This may further exacerbate the infection. All these lead to underestimation of its incidence and therefore the current prevalence of nocaridal infection in developing countries like India is still uncertain. In this study, we describe 164 patients with culture-proven Nocardia infections from various specimens of ocular infections. Besides epidemiological details such as predisposing factors, demography, and seasonal variation, the results of in vitro anti-bacterial susceptibility and efficacy of conventional diagnostic techniques in diagnosing nocardiosis are also described. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest series of ocular nocardiosis reported worldwide.

Materials and methods

Patients

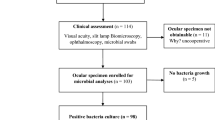

This retrospective study was conducted at Aravind Eye Hospital, Coimbatore, India. Cases with culture-proven ocular nocardiosis were identified from ocular microbiology laboratory database among all ocular specimens collected from patients with keratitis (Figure 1a and b), endophthalmitis (Figure 1c and d), scleritis, wound infiltrate, suture infiltrate, etc., between March 1997 and February 2005 and included for epidemiological study.

(a) Slit-lamp biomicroscopic diffuse view showing Nocardia keratitis with superficial infiltrates forming string of pearls or wreath pattern. (b) Healing patchy infiltrates. (c) Early postcataract surgery infection; tunnel infiltrates iris nodule and hypopyon. (d) Infection progressing with larger nodule and fibrinous pupillary membrane obscuring IOL. (e) Corneal scraping inoculated on to blood agar showing dry granular colonies of Nocardia. (f) Vitreous specimen inoculated on to blood agar showing colonies of Nocardia.

Microbiological methods

The microbiological records for all patients infected with Nocardia species were reviewed. Information on specimen type, age, sex, seasonal variation, coexisting infections, results of each diagnostic techniques, and in vitro anti-bacterial susceptibility patterns were recorded and analysed. During the 8-year study period, 8770 various clinically suspected ocular specimens were received from 8469 patients and processed for microbiological investigations. Culture methods involved direct inoculation of specimens on to 5% sheep blood agar, chocolate agar, non-nutrient agar, potato dextrose agar, thioglycollate, and brain–heart infusion broth. The inoculated potato dextrose agar was incubated at 25°C to isolate fungi and examined daily up to 3 weeks. To isolate bacteria, inoculated sheep blood agar plates were incubated under aerobic and anaerobic conditions; chocolate agar was incubated with 5% carbon dioxide, and thioglycollate and brain–heart infusion broth aerobically at 37°C. Non-nutrient agar was incubated with seeded Escherichia coli suspension overlay to identify Acanthamoeba. Microbial cultures were considered positive only if growth of the same organism was demonstrated on two or more solid media, or there was confluent growth at the site of inoculation on one solid medium with consistent direct microscopic findings. The isolated Nocardia species were further confirmed and all laboratory methods were followed by standard microbiological procedures.17, 18 If further specimens were available from cases, they were also subjected to Gram stain, 10% KOH wet mount, and acid-fast stains (modified Kinyoun's method).

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns were studied for the confirmed isolates of Nocardia by agar disc diffusion method (Kirby–Bauer method),19, 20 following guidelines by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. The antibiotics used were amikacin (30 μg), tobramycin (10 μg), gentamycin (10 μg), cefazolin (30 μg), cephotaxime (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), chloromphenicol (30 μg), vancomycin (30 μg), and co-trimaxazole (25 μg).

Data analysis

Isolation rate estimates are provided with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with normal approximation. Annual and monthly isolation rates were calculated and presented in line diagrams for trend analysis. Statistical significance of trend was tested using χ2 test for trends. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 164 nocardial isolates were identified among 5378 culture-positive specimens and the isolation rate was estimated to be 3.1% (95% CI: 2.6, 3.6%) during the 8-year study period. The rest of the pathogens included bacteria (44.1%), fungi (47.1%), mixed (5.2%), and Acanthamoeba (0.6%) (Table 1).

The annual isolation rate ranged from 2.3% (2001) to 3.9% (1998) (Figure 2). There was no statistically significant annual trend in the isolation of Nocardia species yield (P=0.623), implying that there was no increase or decrease in isolation rate over years. Similarly, when the monthly trend was analysed, the isolation rate ranged from 1.9% (March) to 4.5% (September) (Figure 3). There was no statistically significant trend (P=0.588) in the isolation of Nocardia species, suggesting that the infection rate remained stable all through the year and was not seasonal. The age in most (61.6%) of the cases yielding Nocardia was between 51 and 80 years. Men were infected more (58.5%) than women (Figure 4).

Among various specimens processed microbiologically, 96 (2.4%) and 29 (13.9%) Nocardia species were isolated from a total number of 4002 corneal scrapings and 208 vitreous specimens, respectively (Figures 1e, f, and 5a). Thirteen (30.2%) isolates of Nocardia spp were isolated from 43 AC specimens. Eight (9%) nocardial isolates were obtained when both AC tap and vitreous specimens were cultured from 91 patients (Table 2). Of the 164 samples that yielded Nocardia species, further specimen could be drawn for Gram staining (Figure 5b) from 125 (76.2%) to 106 (64.6%) for KOH. Only 27 (16.5%) specimens could be subjected to modified Kinyoun's staining (Table 3; Figure 5c).

(a) Sabouraud dextrose agar inoculated with corneal scraping showing pigmented, glabrous, and folded colonies of Nocardia. (b) Gram-stained smear of corneal scraping showing Gram-positive, beaded branching filaments of Nocardia. (c) Modified acid-fast staining showing acid-fast branching filaments of Nocardia.

Upon analysis of antibiotic susceptibility pattern, 65.8 and 61.5% nocardial isolates showed resistance towards cefazolin and ampicillin, respectively. Further analysis showed that maximum number of isolates were found to be sensitive to amikacin (98.7%) and ciprofloxacin (90.2%) (Figure 6).

Discussion

Nocardia are bacterial members of the order actinomycetes, causing localized or disseminated infection referred as nocardiasis. Ocular nocardiosis remains difficult to recognize, thereby leading to misdiagnosis and underestimation of its incidence. In this study, the isolation rate of Nocardia was observed as 3.1%. The other studies on ocular nocardiosis reveal a lower isolation rate. These studies have analysed isolation of Nocardia from either keratitis or endophthalmitis. We have analysed nocardial isolation from both keratitis and endophthalmitis cases. In this study, the isolation rate from keratitis cases was found to be 2.4% as we have isolated majority of Nocardia from corneal ulcers. Even this was significantly high when compared with Sridhar et al10 from Hyderabad, who in their study had reported the isolation rate as 1.7%. The other contemporary studies also revealed a similar isolation rate. Srinivasan et al21 from Madurai had reported an isolation rate of 1.6%, and Bharathi et al9 from Tirunelveli had reported an isolation rate of 1.4%. In a large-scale study, Haripriya et al4 from Madurai had reported 16.8% from 196 postoperative endophthalmitis cases.

Analysis of annual isolation did not reveal any increase or decrease in the isolation rate over years. Some earlier reports have pointed out a possible increase in the incidence of nocardial infection. However, Matulionyte et al2 in their study had reported that Nocardia remained infrequent and less isolated organism over a period of 15 years. Similar findings were observed in some European countries.22, 23 An increased awareness of an ongoing infection and its causative organism, which requires additional media other than the conventional media for its isolation, may improve its isolation rate as in case of Acanthamoeba keratitis.24 Nocardia can be isolated from all primary isolation media (eg blood agar); hence, an increase of epidemic proportion only can raise the annual incidence. Further analysis of the monthly incidence also did not show a statistically significant seasonal variation (P=0.588). Bharathi et al9 too in their study did not observe a statistically significant increase in the incidence of nocardial keratitis in any season. A moderate increase in cases was observed in September, but no significance can be attributed to this raise.

Most of the patients affected were elderly adults from 51 to 80 years of age. Although they did not have any underlying immunodeficient condition, which may predispose to nocardial infection, their general immune status may be low in these age groups, which make them vulnerable to nocardial infection. Matulionyte2 had observed that 16 of the 20 patients with nocardial infection had one or other underlying immunodeficient condition.

Men were more affected than women in this study. In most of the published reports, male predominance was clearly delineated.4, 9, 10, 11 Although no apparent reason could be attributed to this observation according to Matulionyte et al,2 it may be related to the hormonal effects on the virulence or growth of Nocardia. Most of the patients in this study were farmers making them vulnerable to soil-related injuries as observed by Bharathi et al.9 This may be an another reason for male predominance.

In this study, Nocardia were suspected after Gram stain examination in 56% of cases. However, among the corneal isolates, the Gram stain positivity was found to be 69.4%. Matulionyte et al2 detected Nocardia in 65% of specimens using Gram stain. A similar finding was observed by Sridhar et al,10 who in their study had reported Gram stain positivity in 10 out of 15 cases of nocardial keratitis. From vitreous specimens, Gram stain could detect only 27.5% of cases. Modified Kinyoun's acid-fast staining revealed 80% of the Nocardia from corneal scrapings and 25% from vitreous specimens in this study. According to Sridhar et al,10 1% acid stain detected Nocardia in all six cases, thus showing 100% sensitivity.

In this study, amikacin was found to be the most effective drug against Nocardia. Earlier studies have indicated using sulphonamides for the treatment of nocardial infections.10, 16, 25, 26 However, the efficacy of trimethoprim–sulphamethoaxazole was less in this study when compared with other conventional antibiotics. In vitro susceptibility pattern showed that more strains were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and cephalosporins.

Sulphonamides with or without trimethoprim were considered as standard treatment for nocardial infections, although there were reports of successful treatments of nocardial keratitis with sulphonamides, resistant to sulphonamides were also observed equally.27, 28 Husain et al27 in their study had observed that all their isolates of Nocardia were susceptible to sulphamethaxazole. However, Donnenfeld et al28 reported the failure of suphonamide therapy in the case of Nocardia keratitis. Bharathi et al9 had reported that approximately 85% of the strains were resistant to sulphonamides. In this study, 53% of the isolates were resistant to sulphamethaxazole and trimethoprim. Amikacin was found to be the most effective drug against nocardial (98.7%) isolates. Sridhar et al10 and Husain et al27 had reported 100% sensitivity to amikacin in their studies. Matulionyte et al2 in their study had described about shifting to alternate drug regimen other than sulphonamides owing to their side effects and lack of efficacy. They observed that amiakcin and imipenem were superior to other drugs in treating nocardial infections. This only proves that amikacin had replaced sulphonamides in the treatment of nocardial infection and probably be the drug of choice for all nocardial infections.

Apart from these two drugs, other classes of antibiotics are also effective against nocardial infection. We observed a sensitivity of 97% to ciprofloxacin among our isolates. Bharathi et al9 had reported that 93.5% of the strains were sensitive to ciprofloxacin. However, others have observed varying resistance among their isolates to ciprofloxacin. Husain et al27 observed that three of the four isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin. Sridhar et al10 in their study had reported that nine of the 13 isolates were sensitive to ciprofloxacin, and Haripriya et al4 from Madurai had reported that 75% of their isolates were sensitive to ciprofloxacin.

Varying sensitivity patterns to aminoglycosides other than amikacin were observed in the literature.1 Although Bharathi et al9 found all their strains sensitive to gentamycin, Haripriya et al4 and Husain et al27 had reported only 50% sensitivity among their isolates to gentamycin. Tobramycin showed a less in vitro activity against nocardial pathogens. In this study, we have observed 68.2 and 60.9% sensitivity to gentamycin and tobramycin, respectively, among nocardial isolates. Although most strains were sensitive to cephotaxime (87.8%), their role may be limited in treating nocardial keratitis, as most of them are systemic antibiotics.29

Available clinical data suggest that Nocardia infections were associated with aggressive clinical course and poor visual outcome. However, early diagnosis and specific treatment had reduced the visual morbidity significantly. Clinical recognition of Nocardia is difficult because of the lack of pathgnomic symptoms. Only a few authors have described a typical clinical picture.11, 13, 14 Although ocular nocardiosis are rare entity, a high index of clinical suspicion should be had in patients with ocular infections owing to trauma or surgery. The organism can be identified by Gram stain in most of the cases. Modified acid-fast stain (1%) should be performed in all suspected cases. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of our nocardial isolates shows amikacin and ciprofloxacin as effective drugs against ocular nocardiosis. Hence, prompt and accurate microbiological diagnosis and early administration of these antibiotics at appropriate concentration may result in a good visual prognosis in ocular nocardial infections.

References

Sridhar MS, Gopinathan U, Garg P, Sharma S, Rao GN . Ocular nocardial infections with special emphasis on the cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2001; 45: 361–378.

Matulionyte R, Rohner P, Uckay I, Lew D, Garbino J . Secular trends of nocardial infection over 15 years in a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57: 807–812.

Eggink CA, Wesseling P, Boiron P, Meis JF . Severe keratitis due to Nocardia farcinia. J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35(4): 999–1001.

Haripriya A, Lalitha P, Mathen M, Prajna NV, Kim R, Shukla D et al Nocardia endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: clincomicrobiological study. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 139: 837–846.

Perry HD, Nauheim JS, Donnenfeld ED . Nocardia asteroides keratitis presenting as a persistent epithelial defect. Cornea 1989; 8: 41–43.

Benedict WL, Lverson HA . Chronic keratoconjunctivitis associated with Nocardia. Arch Ophthalmol 1944; 32: 84–92.

Peniket EJK, Rees DL . Nocardia asteroides infection of the nasolacrimal system. Am J Ophthalmol 1962; 27: 294–298.

Basti S, Gopinathan U, Gupta S . Nocardia narcotizing scleritis after trauma. Successful outcome using cefazolin. Cornea 1994; 13: 274–276.

Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Vasu S, Meenakshi R, Chirayath A, Palaniappan R . Nocardia asteroides keratitis in South India. Ind J Med Microbiol 2003; 21: 31–36.

Sridhar MS, Sharma S, Reddy MK, Mruthyunjay P, Rao GN . Clinicomicrobiological review of Nocardia keratitis. Cornea 1998; 17: 17–22.

Rao SK, Madhavan HN, Sitalakshmi G, Padmanabhan P . Nocardia asteroides keratitis: report of seven patients and literature review. Indian J Ophthalmol 2000; 48: 217–221.

Rajaduraipandi K, Arun S, Revathi R, Kalpana N . Pseudomonas & Nocardia keratitis associated with soft contact lens—a case report. Journal of TNOA 2000; 41: 81–82.

Hirst LW, Harrison GK, Merz WG, Stark WJ . Nocardia asteroides keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1979; 63: 449–454.

Henderson JW, Wellman WE, Weed LA . Nocardiosis of the eye: report of case. Mayo Clin Proc 1960; 35: 614–618.

Zimmerman PL, Mamalis N, Alder JB, Teske MP, Tamura M, Jones GR . Chronic Nocardia asteroides endophthalmitis after extracapsular cataract extraction. Arch Ophthalmol 1993; 111: 837–840.

Saubolle MA, Sussland DN . Nocardiosis: review of clinical and laboratory experience. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41: 4497–4501.

Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS . Bailey & Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology, 11th ed. Mosby: St Louis, MO, 2002.

Collee JG, Fraser AG, Marmion BP, Simmons A (eds). Mackie & McCartney Medical Microbiology, 14th ed. Churchill Livingstone: New York, 1996.

Bauer AW, Kirby WWM, Sherris TC, Truck M . Antibiotic susceptibility tests by standard single disc method. Am J Clin Pathol 1966; 45: 493–496.

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Approved Standard. M2-A5. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests, Fifth edition. NCCLS, Villanova, PA, 1995.

Srinivasan M, Gonazales CA, George C, Cevallus V, Mascarenhas JM, Asokan B et al Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of cornel ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br J Ophthalmol 1997; 81: 965–971.

Farina C, Boiron P, Ferrari I, Provost F, Goglio A . Report of human nocardiosis in Italy between 1993 and 1997. Eur J Epidemiol 2001; 17: 1019–1022.

Pintado V, Gomez-Mampaso E, Fortun J, Meseguer MA, Cobo J, Navas E et al Infection with Nocardia species: clinical spectrum of disease and species distribution in Madrid, Spain 1978–2001. Infection 2002; 30: 338–340.

Manikandan P, Bhaskar M, Revathy R, John RK, Narendran V, Panneerselvam K . Acanthamoeba keratitis—a six-year epidemiological review from a tertiary care eye Hospital in south India. Ind J Med Microbiol 2004; 22: 226–230.

Hudson JD, Danis RP, Chaluvadi U, Allen SD . Posttraumatic exogenous Nocardia endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 135: 915–917.

Davitt B, Gehrs K, Bowers T . Endogenous Nocardia endophthalmitis. Retina 1998; 18: 71–73.

Husain N, Matoba AY, Wilhelmus KR, Jones DB . Isolation and therapy of Nocardia keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1995; 3(Suppl): S155.

Donnenfeld ED, Cohen EJ, Barza M, Baum J . Treatment of Nocardia keratitis with topical trimethoprim-sulfamethaoxazole. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 99: 601–602.

Sharma S, Sridhar MS . Diagnosis and management of Nocardia keratitis. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37: 2389.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Department and institution to which the work attributed: Department of Microbiology, Aravind Eye Hospital & Post Graduate Institute of Ophthalmology, Avinashi Road, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manikandan, P., Bhaskar, M., Revathi, R. et al. Isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Nocardia among people with culture-proven ocular infections attending a tertiary care eye hospital in Tamilnadu, South India. Eye 21, 1102–1108 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702513

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702513

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Filamentous gram-negative bacteria masquerading as actinomycetes in infectious endophthalmitis: a review of three cases

Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection (2018)