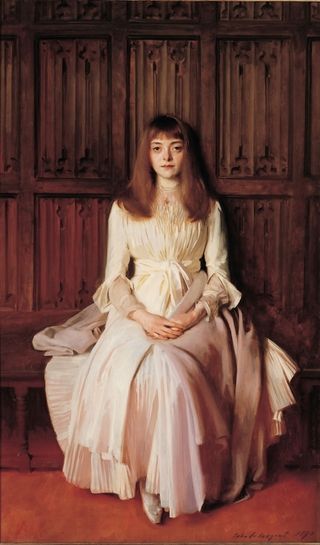

John Singer Sargent's paintings can stop a person in her tracks. At the peak of the revered artist's turn-of-the-century career, only members of America's high society could pay the exorbitant fees that his sensitive, evocative portraits commanded. Some of Sargent's works, like the then-scandalous Madame X, have claimed their own fame. But others have endured more quietly and mysteriously—until now.

In Sargent's Women: Four Lives Behind the Canvas, author Donna Lucey sought to understand four of the women whose likenesses Sargent recorded. While narrowing it down from the 900 paintings and 1,000 sketches that made up his oeuvre was "incredibly hard," Lucey eventually decided on characters like enigmatic railroad heir Elsie Palmer and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum's iconoclastic art-collector namesake. Why? "I’m interested in eccentric women and women who are pushing the boundaries. And of course, these women have never gotten the credit they deserve."

We spoke to Lucey about championing these unconventional women, the eight-year process of piecing together their intricate lost stories, and the stormy brew of scandal and repression that affected these women—and Sargent himself.

How did you decide which of Sargent's subjects to focus on?

In my last book, Archie and Amélie, the Archie of the title is Archie Chanler, whose sister Elizabeth was painted by Sargent. So I knew of her amazing story, and I began to wonder about other women he had painted and what their stories were. It took me over a year just to decide which characters I wanted to pursue. But my rules were rather simple. I wanted to have, of course, great stories. I wanted to love the painting too. I wanted to write it from the inside out, so I wanted only characters who had left behind a huge cache of letters, diaries, original documents. People asked me, why aren’t you doing Madame X? Well, she didn’t leave behind any papers. These other women—their stories were so amazing. My interest is in writing about unconventional women.

For example, Isabella Stewart Gardner—she has her museum, but she's an incredible personality. Today she would be the CEO of some major corporation. She was just unstoppable. But she’s never really gotten the credit, even as an art collector. Art historians always give Bernard Berenson, who was the connoisseur, much of the credit for her collection. And of course, he did help her find things, but she knew exactly what she wanted. She turned down lots of things that he wanted her to buy. She was the one who picked out a Vermeer herself.

Most of your book is about women Sargent painted. But the section about Sally Fairchild’s portrait tells us more about her sister, Lucia. How did that happen?

Sally was the golden girl; she’s the one that everybody loved. And Sargent painted her a number of times. He was a friend of the family. Everybody adored Sally—she’s the beautiful one. And Lucia was the kind of ugly-duckling sister who’s sitting in the background. But she was the one who kept a diary of everything that Sargent said, how he painted—and she just adored him. So she’s the one who, because of that painting, decided to become an artist herself.

And oddly, Sally’s trajectory went quite differently. She led an uninspiring life. So what I loved was that unexpected quality. When I was doing research, I went to the Boston Athenaeum. I was looking for an uncataloged scrapbook, which the librarian had never seen, and there in the first page was a picture of Sargent. Behind him, like a spy, there was Lucia, watching him. I think Sargent chose the wrong sister—he should’ve painted Lucia.

Sargent isn’t the focus of the book himself. What did you learn about him in your research?

Everything about him is fascinating, but he remains a bit of an enigma. First of all, he had all these papers burned after he died, and it seems like he was probably gay, though his past biographers take pains to say that he was this hearty heterosexual. But he had a very keen interest in the male nude. He kept a whole cache of male nudes locked away so no one could see them, and he had long-term relationships with men who lived with him and worked for him, and he had a portrait hanging on his dining room wall of Albert de Belleroche, who was someone he painted with and traveled with—he referred to him as "baby." So I felt a little bit sorry for Sargent, because there was this element of repression, that he always had to hide who he was.

I think that I was also surprised at how all of the paintings were staged: He would choose the dresses that the women would wear. If he didn’t like their dresses, he would just take a piece of fabric and position it so it looked like a dress. Everything was important.

Is there something you think modern women might particularly appreciate in reading about these women?

I’m hoping that young women are going to read this book because, with the exception of Isabella, it’s all about young women. Elsie Palmer was 17 when she was painted, Sally Fairchild was 21, Lucia, watching, was 18, and Elizabeth Chanler was 27 years old. Belle was older, and she was so feisty and wonderful. But all of them did something that no one expected and that’s what I love. They all broke convention in some way. Poor Elsie Palmer had been groomed her whole life to be the handmaiden of her mother, who was sickly, and then she had this horrible love affair with mother’s best friend's husband, who then dumped her for her younger sister. Then, she became her father's caretaker—he expected her to take care of him for the rest of his life. And then one day she just announces, I’m leaving.

Lucia's parents didn’t want her to marry the man she married, didn’t want her to become an artist, and then she led this difficult life of being an artist and having this husband who decided it was beneath him to earn money. Her extraordinary story—of having multiple sclerosis, and having to take care of and support both of her children while her husband is screwing all of his models. And Elizabeth—everyone thought she would never marry; she was always supposed to take care of everybody else. When her mother died, she was nine years old and had to become the surrogate mother for her 10 siblings. Then, a year later, she’s sent off to the Isle of Wight and is orphaned, then contracts this terrible hip disease and is literally strapped to a board for two years. She’s thought to be this pathetic creature. And lo and behold, she falls in love with her best friend’s husband.

Belle loved flouting Boston, which was so prim and proper, starting from her designer clothes to dancing with men who weren’t her husband, and flirting with everyone. And doing things like having prizefighters come to her house and pose half-naked while she was having tea. Society in Boston found her repulsive. And what does she do? Create a museum so magnificent that even all of them had to be in awe at what she did.

All these women were passionate; they followed their desires, even if it led them to trouble, even if it meant they had to suffer the consequences of society’s restrictions. They weren’t afraid to say: I’m going to be who I am and take the consequences.

This interview has been edited and condensed.