Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Ancient reptilian carnivores that resembled modern crocodiles were fearsome hunters, but their scaly armor and sharp teeth couldn’t protect them from parasites, scientists have discovered.

Paleontologists recently unearthed rare evidence of parasitic infection in a reptile that lived around 252 million to 201 million years ago during the Triassic Period. The animal may have been a phytosaur — a long-snouted, short-limbed predator. Researchers didn’t find the parasites in phytosaur bones or teeth; rather, they retrieved them from a nugget of fossilized feces, known as a coprolite.

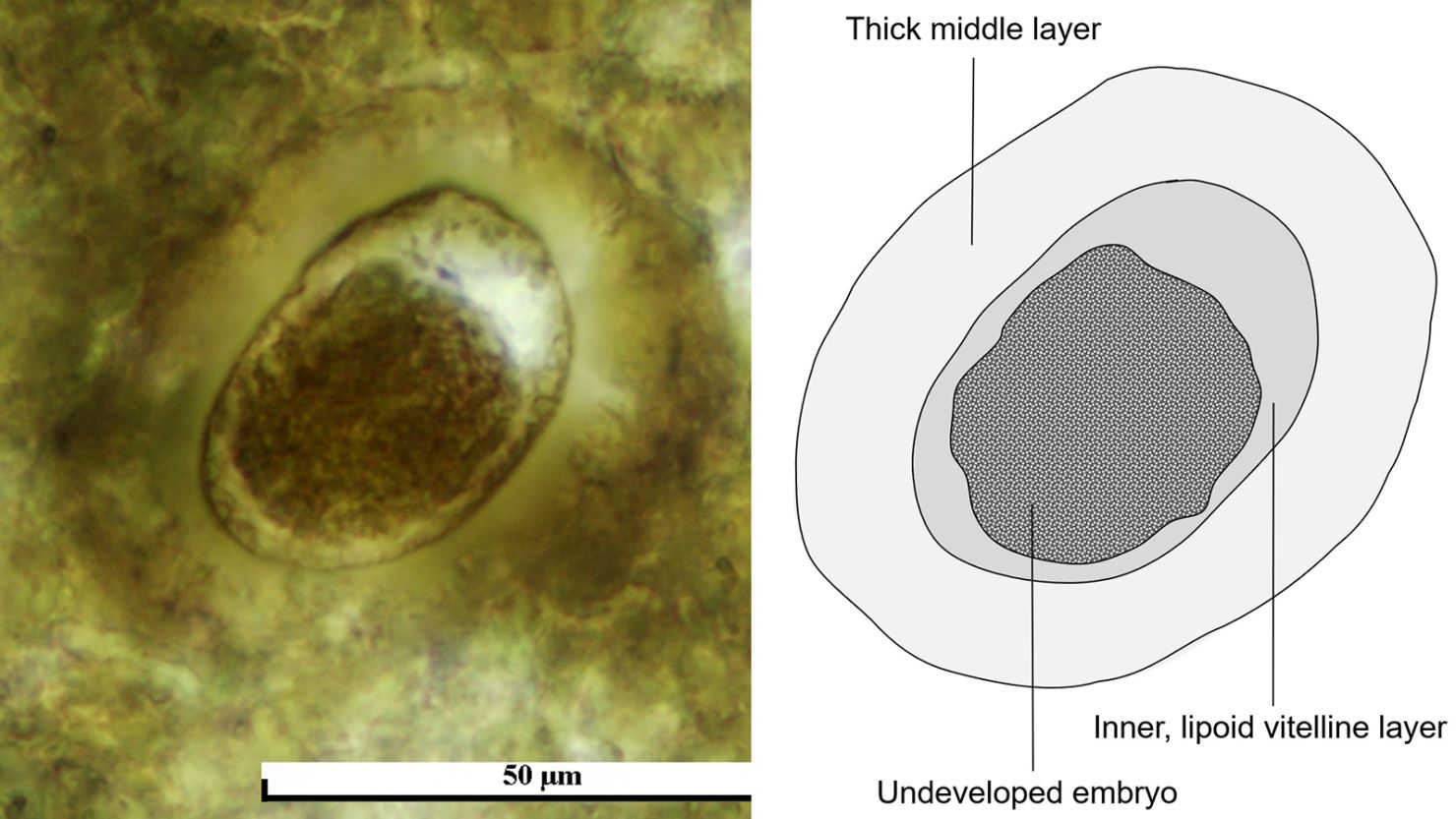

When scientists sliced apart the preserved poo, found at a site in Thailand that’s about 200 million years old, they found tiny organic structures resembling eggs. The objects measured 0.002 to 0.006 inches (50 to 150 micrometers) long, and closer analysis revealed that they represented at least five different types of parasites.

This finding is the first evidence of parasites in a terrestrial vertebrate from Asia during the Late Triassic, the researchers reported Wednesday in the journal PLOS One. The specimen is also the first coprolite from this time and place to contain multiple parasitic species — including nematodes, a group of parasitic worms that is still around today. Modern nematodes commonly infect plants as well as animals, and are found in a variety of mammals, fish, amphibians and reptiles — including alligators and crocodiles.

“Our results give us new ways to think about the environment and way of life of old animals,” said lead study author Thanit Nonsrirach, a vertebrate paleontologist in the department of biology at Mahasarakham University in Kham Riang, Thailand. “In previous studies, only one group of parasites was found in a single coprolite. However, our current study shows that a single coprolite can contain more than one type of parasite.” The analysis suggested that the animal hosted numerous parasitic infections.

‘Hard, smooth and grey’

Scientists collected the coprolite in 2010 from the Huai Nam Aun outcrop in northeastern Thailand. During the Triassic, this would have been a brackish or freshwater lake or pond inhabited by diverse groups of animals, including sharklike fishes, turtle ancestors and other reptiles, and primitive amphibians called temnospondyls, Nonsrirach told CNN in an email.

“Such conditions were conducive to the transmission of parasites,” he said.

The fossilized poo, cylindrical in shape, measured about 3 inches (7.4 centimeters) long and 0.8 inches (2.1 centimeters) in diameter. The specimen’s surface was “hard, smooth and grey in colour,” the study authors wrote. Coprolites may not look very impressive on the outside, but buried inside them are secrets about “who ate whom” in ecosystems of the distant past, said paleontologist Martin Qvarnström, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of organismal biology at Uppsala University in Sweden. Qvarnström was not involved in the new research.

“Surprisingly, coprolites often contain fossils rarely preserved elsewhere,” Qvarnström said in an email. “These include muscle cells, beautifully preserved insects, hair, and parasite remains. But despite being treasure chests in this regard, coprolites are opaque, so identifying their inclusions can be challenging. Detective work is also needed to find out who produced the now fossilised droppings, which is arguably the trickiest part of studying coprolites.”

Coprolites’ size, shape, location and contents tell scientists which extinct animal group might have produced the poo. For example, certain fish with spiraling intestines poop out what eventually become spiral-shaped coprolites, according to Nonsrirach. And amphibians and reptiles “generally make coprolites that are mostly cylindrical,” he explained.

There were no bones in the coprolite, hinting that its owner had a digestive system powerful enough to dissolve them. This physiological trait is known in crocodiles, but the earliest crocodilians wouldn’t appear for another 100 million years or so, and crocodile fossils haven’t been found at this location, according to the study.

However, “it’s plausible that the coprolite originated from an animal similar to crocodiles or one that evolved alongside them, like phytosaurs,” Nonsrirach said. What’s more, phytosaur fossils were previously found near the site where the coprolite was excavated.

Eggs and cysts

At first glance, phytosaurs seem almost indistinguishable from crocodiles. Both have elongated and toothy jaws; heavy bodies topped with rigid scales; and long, powerful tails. One notable difference is that phytosaurs’ nostrils are perched on a bony ridge below their eyes, while crocodiles’ nostrils are at the end of their snouts, according to the University of California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley.

But while these animals may be virtual lookalikes, they aren’t closely related. Their copycat body plans are the result of convergent evolution, in which unrelated animals independently evolve similar features.

When the scientists sliced the coprolite into thin sheets and studied them under a microscope, they found five types of organic structures: some spherical and some ellipsoid. One object that was sliced in half had an outer shell and an embryo inside, and the researchers identified it as an egg of a parasitic nematode in the order Ascaridida.

Another object had “a well-developed shell and organized bodies within the shell,” and could be another type of nematode egg, according to the study. The rest were identified as eggs from unknown worms and cysts from single-celled parasites.

“Studying the remains of parasites in coprolites is important since it provides us with rare insights into ancient parasite-host relationships,” Qvarnström said. “Thanks to the coprolite data, we can investigate when such parasitic relationships arose and how parasites and their hosts may have co-evolved through time.”

However, it’s unknown whether carrying the parasites made the reptile sick, Nonsrirach added.

“The determination of the animal’s health status cannot be determined by only the observation of the parasite contained within its coprolite,” he said. “Parasites have the ability to use their host as a way of development without causing disease to the host animal.”

The reptile may have acquired its community of parasites by eating different types of infected prey, according to the study.

“This event raises interesting questions about how prey animals and parasites interact with each other. It suggests that parasites may have been inside the bodies of prey before they were eaten,” Nonsrirach said. “This new point of view gives us a deeper understanding of how past ecosystems were connected and how they affected the lives of prehistoric animals.”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works magazine.