The man on the fifth floor wanted pizza.

Four nights in a row, a clerk from Le Rose Hotel called, and four nights in a row, the restaurant owner dispatched a waitress with a Margherita pie for the guy in 5-D. Why someone in a hotel room overlooking the Adriatic wanted delivery didn't concern the restaurant owner. Oliver Laghi was a businessman and this was Rimini, where businessmen didn't ask too many questions or make too many moral judgments.

Two hours south of Venice, three hours northeast of Rome, a world away from any notion of office or deadline, Rimini beckons and teases with its cloudless summer skies and vast sandy beaches, but at night, away from the T-shirt shops and gelato stands that line the main drag, there exists another resort of less innocent but no less potent allure and economic vigor—the one of all-night parties and easily accessible cocaine and prostitutes.

So it was mid-February? So it was the resort's off-season? Some guy wants to hole up and look at waves and chew crust in the dark—who was Laghi to wonder? Business is business.

On a Friday evening, the 13th of February 2003, the clerk from Le Rose Hotel called again. The fifth night in a row and this time the guy wanted an omelet. This time, the clerk told Laghi who the guy on the fifth floor was.

Imagine Babe Ruth putting away a few hot dogs around the corner and he calls and could you join him? Imagine Michael Jordan's car is stalled, and would you mind bringing some jumper cables? Imagine you're a businessman who doesn't ask too many questions or make too many moral judgments and that you have just speed-walked two blocks and you're holding the omelet you whipped up yourself—Fontina cheese and ham, two eggs, no toast, no potatoes—and your country's greatest and most beloved athletic hero opens a door and stands in front of you, bloated, grayish, unkempt. Imagine he hasn't bathed in days. Imagine terror in his eyes, confusion. Imagine gazing at exhaustion so deep you think you might weep.

Imagine you start babbling. "I have followed your career!" Laghi exclaimed. "The Tour! The Giro d'Italia!" Imagine you can't help it. The businessman couldn't. He wept.

The hero had always confounded. The unthinkable acceleration, the perfect gesture at the most unlikely moment—that's what defined his greatness. That's one reason people loved him. He attacked when others retreated, fought when others quit. Even now, wrecked, malodorous, terribly sick, he did it again. The impossible. He smiled. A great, dazzling smile. A miracle, really. He patted Laghi on the back. There, there. No need to cry.

Laghi couldn't stop. "Please," he said, "accept the omelet for free." Then Marco Pantani, one of the greatest cyclists Italy has ever known, one of the greatest climbers in history, now disgraced, now dying, did something else miraculous. He laughed. He also insisted on paying.

Imagine you have a chance to ease the pain of a demigod, but you are a businessman, and your restaurant is busy. Laghi hated to go. Would it be okay, he asked, if he came back to visit tomorrow? Tomorrow was Valentine's Day. Laghi would bring more food. They could talk about cycling. They could talk about whatever Pantani wanted to talk about. Would that be okay?

The hero's smile was gone now. Huge efforts exact huge costs. They always had with Pantani. The exhaustion had returned. And sadness. Great sadness. Laghi remembers it: "Molto triste."

"Sure," the hero said, very quietly. "Sure. Come tomorrow and we'll talk some more."

Imagine you'll never see your hero alive again. Imagine no one will. Now, imagine a nation that can't stop chasing ghosts, that won't stop weaving reassuring little lies. Imagine an entire country that can't face a simple truth.

THE ANGELS OF THE MOUNTAINS

Cycling's greatest climbers are different. The greatest climbers, the pure climbers—those who can ascend any given mountain faster than even the most accomplished all-around champions—these men are not just lighter and smaller and more sinewy than other cyclists, who are themselves lighter and smaller and more sinewy than most humans. The pure climbers are not just positively spidery in their ability to scale steep routes. No, these great climbers—the Angels of the Mountains, as they are known—are different because they are so odd. Exquisitely tuned. Delicate. Fragile.

Angels are rarely champions, and champions are rarely Angels. It is the calm and the predatory and the brilliantly conniving and the consistent who win major races. But it is the Angels who make us forget the science of the sport—the computer-refined carbon frames and the diets calibrated to the tenth of an ounce and the wind-tunnel-tested, custom bodysuits—and force us to witness the art. It is the Angels who attack absent any apparent regard for consequences, who find fearlessness on paths where others hang back, who pedal into arrogant climbs and desperate, primal pursuits. The great champions calculate and focus and hold something always in reserve. The Angels inspire and baffle and alarm.

Angels tend to be held in awe because when they do win, the way they do it is so simple and primitive, and as basic and as easily comprehensible as going faster than anyone else where it's basically impossible to go fast. Because of this, they tend to be suspected of cheating. And they tend to come to bad ends: hermetic isolation, premature deaths, suicide.

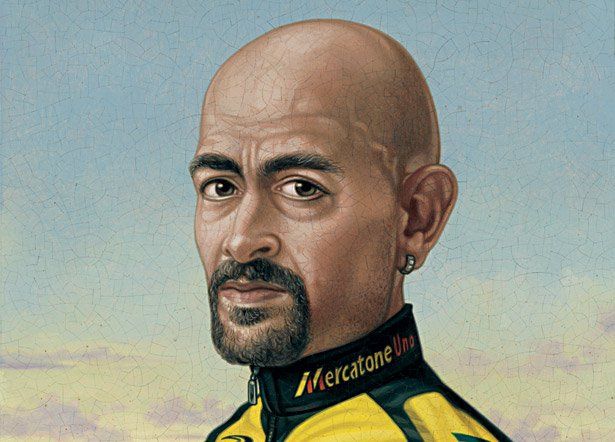

Marco Pantani stood apart. Even among these frail seraphs—a group prone to exposed nerve endings and thrilling, evanescent victories and unfortunate demises—he stood apart. No Angel ever ascended more swiftly. None ever fell so far, so fast.

"The best climber in the history of the sport," Lance Armstrong said after his rival died.

"The cursed champion," says Mario Pugliese, a journalist, and a friend of Pantani's since each was 11 years old.

For seven years, Pantani seduced a cycling-mad country, vexed a sporting establishment as few cyclists ever have, and wounded legions of fans who refused to believe how fast their hero was falling. In 1997, Pantani climbed the iconic and fearsome Alpe d'Huez faster than anyone in history. The next year, he won the Giro d'Italia (the Tour of Italy, his homeland's biggest race and the second-biggest race in the world) and the Tour de France, one of only seven men to have ever achieved the double triumph in the same season, and the last. With his Tour victory, he rescued the sport from irrelevance and destruction in its most scandal-plagued hour.

He was a cheater. He was an innocent victim. Sensitive and cruel. Loving and arrogant. A villain. A hero. He saved the Tour de France. He brought shame on cycling. He inspired others. He destroyed lives.

This is what people say, and it's all true.

"I'M TERRIFIED MARCO WILL FALL"

The six-year-old boy was clumsy, accident-prone, always moving but seldom with much grace. A skinny child with a fearsome sweet tooth (he loved Nutella and the apricot jam his mother, Tonina, made especially for him, and at night he snuck down to the kitchen and licked mascarpone from the bowl), a thumb-sucker, as he would be until he was eight years old, a loner with big eyes and big ears. A sweet little boy, a mama's boy, really. In another time, in another country, a doctor might have prescribed Ritalin. But this was Cesenatico, Italy, in 1976, and so Tonina Pantani bought her young son, Marco, a red two-wheeler because she thought it might calm him down.

It didn't. Three times as a child, he was hit by cars while cycling. Tonina says she knew every time, even before she heard. "I would say at work, 'I'm terrified Marco will fall today,'" she says. "Then I'd come home and my husband would tell me, 'Marco fell today.'"

By the time he was 12, he had traded in the little red two-wheeler for a racing machine, and the rest of his life receded. Every day, he'd ride to the distant hills of Emilia-Romagna, and every day upon his return, he'd bring his bicycle inside to wash it in the bathtub. Afterwards, he'd let it dry in the hallway on the second floor. At night, he'd bring it into his bedroom.

"It bothered me because it made the walls dirty," Tonina remembers. "We had a garage. He could have kept it in the garage." She fretted, and loved, but mostly she worried. Marco hated that, she says. Marco promised that he would call if he were in trouble. So that when she didn't hear from him, she shouldn't worry. She worried, anyway.

His father, a plumber, worried for different reasons. At the end of Marco's first year on a racing bike, Paolo Pantani told his son that if he loved biking so, he should devote himself to it for another year. At the end of the year, if cycling hadn't worked out, Paolo would teach Marco plumbing.

It worked out. At 20, in 1990, Pantani won the amateur version of the Giro d'Italia, including two stage victories in the jagged Dolomites. By the time he was 24, he had turned professional, placed second in the Giro and third in the Tour de France. In the mountains, with his feral attacks and ridiculous, out-of-the-saddle surges, he was incomparable. He had a following, and a nickname. Because of his youth and the size of his ears, which was exaggerated because he was prematurely balding, cycling fans and cyclists called him Elefantino, or Baby Elephant, which he hated. He was an Angel now, one with prodigious talent and horrible luck. In the October 1995 Milan-Turin race, a jeep drove onto the course and Pantani hit it head-on, shattering his left leg. People said he would never race again.

"THE ONES WHO LET MARCO DIE"

His mother is crying, and who can blame her? Marco was her only son, and it hasn't even been five months since his death. Outside the locked front gates of the family villa in Cesenatico, Pantani's birthplace, 15 miles up the coast from Rimini, a car full of fans from some far-flung province, or maybe from another country, stops so they can shoot videotape, then snap photographs, then just stare.

Tonina ignores the car. She's learned to do this. Behind her, inside the house built with her son's enormous cycling wealth, airing out, opened for the first time since she heard the horrible news, is the wing where he stayed. There is his tanning booth, and his bedroom and his bathroom with his Lion King cologne still on the counter of the sink, and the chamber that has become his shrine, filled with photos and keepsakes.

There is the great champion sucking his thumb as an eight-year-old and peering over his shoulder with embarrassment; there is the hero standing with the Pope, and a tiny, red-plastic Volkswagen a little boy from England sent him. Children always adored him, even at the end. There's a framed yellow jersey from the Tour de France. A photo of the cyclist passing Lance Armstrong on a steep, narrow road.

It is a hot day, windless, cloudless. On the front lawn, a grass-covered wire sculpture of a bicyclist. Behind the sprawling structure, a swimming pool. On one side of the villa, fields of corn. On the other side, a vineyard. Looming in the mid-distance, the hills into which he would disappear as a little boy, pedaling to places Tonina couldn't imagine, to places that always worried her.

She sits on the porch, underneath a flat, tinny summer sun. She is not private in her grief. She never has been. In an interview shortly after he died, she said he had been murdered. She blamed members of his cycling team. She lashed out at officials in the cycling community. She said she would name names. Since then, Marco's manager, who took him on in 1998 and stayed with him until he died, Manuela Ronchi, has been present to monitor Tonina's interviews. She is here now. The manager, it turns out, is measured and diplomatic only when compared with Tonina.

"There was no proof," Ronchi says. "Not even an idea of proof. In five years, he never, never tested positive. If not for that scandal, he would have won four Tours! And he would have won by four hours, not two minutes!"

Ronchi is grieving, too. And who can blame her? Pantani was more than a client. He was a friend, in some ways like a little boy to her, a little boy in desperate trouble. Someone crying for help. Pantani had that effect on people.

I ask if anyone could have saved him.

"A woman," Ronchi says, and at this Tonina nods. "A woman who really loved him." His mother weeps bitterly.

They blame Pantani's Danish girlfriend, Christina Jonsson, who, it should be noted, admitted to sharing cocaine with him for years and after his death gave—or sold—an article to L'Hebdo, a Swiss weekly, which was headlined, "We Did Drugs for Love." They blame the journalists who they say sensationalized the doping charges. They blame the cycling powers for making Pantani a scapegoat for the sport's woes. They blame themselves.

Others blame them, too. Mario Pugliese, the lifelong friend who, for the past seven years, has been a reporter for La Voce di Romagna, the regional paper of Cesenatico, says Tonina and Ronchi were more interested in Marco's lucrative cycling career than in protecting his life. Pugliese also blames his editor for not allowing him to write a story addressing Pantani's addiction. Michel Mengozzi, a friend who repeatedly tried to get Marco to quit drugs and who, just a few months before Pantani's death, journeyed to Cuba to retrieve him from a vacation gone horribly wrong, blames the staff at the hotel where he spent his last week. When he sees a piece of stationery I carry from Le Rose Hotel, he says, "These people aren't good. These are the ones who let Marco die."

Some of the people I talk to in Cesenatico and Rimini blame the local cops, for not arresting the national hero after a series of car accidents, when they knew or should have known he was using drugs, for not scaring him straight. Many blame, naturally, the drug dealers who supplied him.

Some fans say he was injected with drugs by jealous competitors while he slept. Or that Italian industrialists orchestrated his downfall because he'd participated in a Citroen advertising campaign. Some of his countrymen blame Cuba. A few Cubans blame Italy. And if people can't find anyone to blame, they invent someone. Vittorio Savini, who managed the racer before Ronchi and now serves as president of Club Magico Pantani, a fan club, says Pantani was targeted by influential and unnameable cycling authorities.

But why, I ask? Why would they single him out?

Wide eyes, arms out, leaning forward.

"That's the question!"

And who wanted him out?

"That's the question!"

Franco Corsini, a Cesenatico restaurateur who tried to save Pantani up till the end, says, "He was a thorn in someone's side. There was a plot to get rid of him. A plot high up. I think maybe he was murdered. Morto! Morto!"

He weeps when he says this. "He died for cycling. His life was cycling." Loud sobbing. "He died for cycling."

There is only one person that the friends and fans and competitors and family of Pantani don't blame for the hero's death. They can't. They can't blame their hero.

"WE ARE IMPRISONED BY RULES"

When bones shatter and flesh rips, what happens inside? As Pantani's body healed from his 1995 crash, did his soul twist in upon itself? Or was that the moment the mask slipped, when the ravenous monster inside the sweet little boy scrabbled out? Is this when the cyclist turned into a junkie?

No one thought to ask then—why would they? Certainly he was different when he returned to cycling. But dangerous? Marked for death? When he came back to the sport he rode with a shaved head and goatee, a hoop earring and a bandanna emblazoned with skull and crossbones. At the beginning of a steep, absurd mountain chase, he would tear off the bandanna and fling it to the ground. Elefantino was dead. Marco called himself Il Pirata. So would everyone else.

He was different, but he was the same. Whereas other top racers rely on packs, use teammates as pacers and protection, Pantani rode as he always had, alone, often from behind, slashing, with no apparent strategy other than sacrificial velocity during the most astonishing climbs.

The prodigious talent, and horrible luck, held. In the 1997 Giro d'Italia, a black cat darted in front of Pantani and he crashed and dropped out. But later that year, on his way to another third-place finish in the Tour de France, after a long and hard day on the road, he scaled the forbidding Alpe d'Huez in 37 minutes, 35 seconds, a record that still stands, even after last year's time-trial up the mountain.

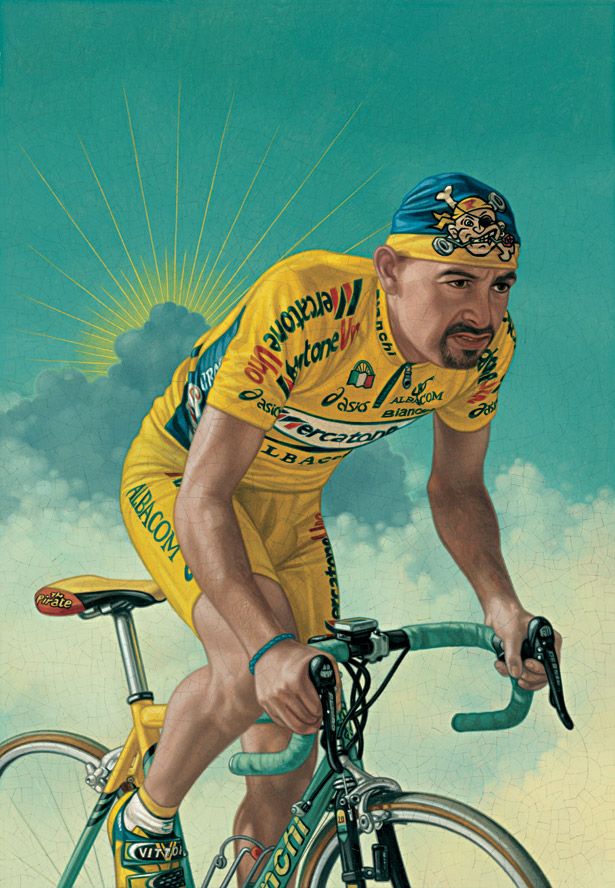

The next year, 1998, Pantani won the Giro, then showed up for a Tour de France that was imploding, after the entire French Festina team was disqualified for blood doping. A sport of cheaters—that's what skeptics had been whispering for years. Now they shouted. Il Pirata, dashing and explosive, quieted them by winning the Tour with spectacular ascents. Here was purity.

The sport needed a hero, and it could not have invented a more engaging one. He chatted with fans, played with children. He presented wonderfully thoughtful, wonderfully strange quotes to journalists. He helped those in need. When an earthquake damaged the town of Assisi, Pantani bought and loaded a truck with food to drive there. It was Pantani who coaxed the troubled Angel of the mountain, Charly Gaul, into making some public appearances again, and rekindling ties with his racing brethren. The Luxembourger had won the Tour in 1958, then grew fat, grew a beard and grew into a grumpy hermit who lived in the woods and refused all visitors. Pantani invited him to rejoin the company of humankind. Was it just kindness, or had Il Pirata peered into the woods and seen himself?

For his victories, Pirata was cheered. For his good deeds, he was admired. For his exceeding and engaging oddness, he was beloved. In Italy, where he was the first paesano to win the Tour since 1965, he was something else altogether.

"He was like the Pope," says Pugliese.

Yes. Just like the Pope, except that Pantani was 28, a sensualist, delighted with the trappings of fame, intoxicated with his singularity. He shot marbles with fans after races, played the horses, hunted pigeons. Other athletes delivered homilies about sacrifice and effort and teamwork. Il Pirata waxed as only Il Pirata could.

"We are all imprisoned by rules," he told Matt Rendell of The Observer (UK) in one interview. "Everyone longs for freedom to behave in the way they see fit. I'm a nonconformist, and some feel inspired by the way I express freedom of thought.There's chaos in everyday life, and I tune into that chaos."

He could afford all the chaos he wanted. From his comeback until the year after his double victory, he made an estimated $10-$15 million, much from endorsements and special appearances. A Spanish organizer paid him $30,000 just to show up for an event. Though he invested—much of it in property in and around Cesenatico and Rimini, including the capacious villa he built for his family—he also didn't deprive himself. He bought his girlfriend, Jonsson, a metallic-blue A-Class Mercedes. He drove a BMW. He danced at Rimini's discos. He was said to enjoy the company of prostitutes. He drank and he used cocaine.

"Yes," says Pugliese. "But a normal amount for a star like him."

Cycling had never seen a disco-dancing, marble-shooting, philosophy-spouting Angel like Pantani. In 1999, he announced his intention to win the Giro-Tour double two years in a row, which no one had ever done. It actually seemed possible. With just two stages left in the Italian race, Il Pirata had built a lead of five minutes, 38 seconds—insurmountable unless something terrible and bizarre happened. It did.

On June 5, shortly after dawn, at the mountain sanctuary of Madonna di Campiglio, cycling's drug inspectors knocked on Pantani's hotel door. Vittorio Savini, then his manager, was with him.

The inspectors told Pantani that his blood hematocrit level—at the time the most accurate indicator of the performance-enhancing drug EPO—was too high.

"We exchanged a look," Savini says, "and then Marco punched his dresser."

Pantani could have served a quiet, if embarrassing, two-week absence from competition then simply have begun racing again, as other cyclists had done. Because the test didn't detect EPO, just the abnormally high level of red-blood cells, racers were technically barred from competition, for their health, until the hematocrit level returned to normal. It wasn't even officially a drug violation.

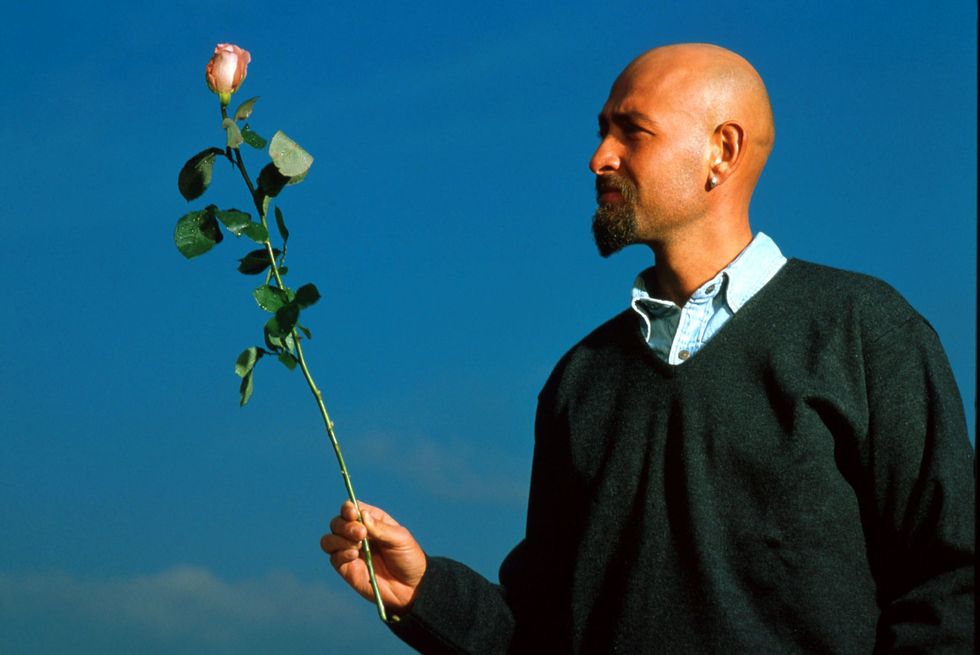

Instead, Pantani claimed he was a victim of a plot, accused authorities of botching the test and fabricating results. He demanded DNA testing (which later proved the tests were accurate). He retreated to his villa. He lashed out. He began speaking of himself in the third person. His cocaine use escalated.

He gained weight, went days without sleeping. He always had driven fast, but now he drove into accidents, once speeding the wrong way down a one-way street and wrecking eight cars. There were long, inexplicable absences.

"He could have faced that problem like an adult, like a man," says Pugliese. "Or he could have faced it like a kid, and tried to escape it, like a kid. And he chose that."

Other cyclists accused of doping have admitted error, focused on recovery and saved their careers. But this was an Angel of the mountains, a man of outsized, enormously fragile pride. Other cyclists found guilty of doping have focused on creating new lives outside the sport. But this was Pantani—man of miracles, patron saint of long odds and steep climbs. He got back on his bike.

In the summer of 2000, he helped teammate Stefano Garzelli win the Giro. Then he took on Lance Armstrong in the Tour de France. Piqued after Armstrong announced that he had allowed Pantani to win a mountain stage (which he, in fact, had), Il Pirata insulted Armstrong in the press. When Armstrong responded that "Unfortunately, Il Elefantino has shown his true colors.I thought he had more class than that," Pantani was enraged, and he let his rage define his riding. He attacked as only a splenetic Angel could—or would.

First, on his way to a stage victory in the Alps, he dropped Armstrong. The next day, he opened up a one-minute gap on a climb early in the stage, and so rattled the normally phlegmatic Texan that Armstrong forgot to eat at a crucial moment, bonked on the Joux Plane ascent and lost two critical minutes to the only rival—Jan Ullrich—who actually posed a threat to Armstrong's Tour aspirations. Later, Armstrong described it as his worst day ever on a bike.

Pantani's attack was thrilling, vengeful, and enormously self-destructive. He eventually was caught, then lost 14 minutes overall. The next morning, he dropped out of the Tour.

The following season, in 2001, police raiding the riders' hotels at the Giro found a syringe with traces of insulin in Pantani's room, and he was banned for another six months. Seven judicial inquiries would eventually be launched against Pantani, including one that charged him with sporting fraud for using performance-enhancing drugs while being a professional athlete.

Money wasn't enough. Adulation couldn't save him. The antidepressants he was taking didn't make him happy. What choice did he have? He would not quit, even as his cocaine addiction consumed him. He got back on his bike.

At the 2003 Giro, he was mobbed every morning at the sign-in. This would have been the perfect moment for his fans to face the truth, to change the narrative they and their hero had conspired to create. But his fans—his country—wanted an Angel. Twice the number of fans surrounded Il Pirata as anyone else, including the leaders. Didn't they know how far he had fallen? Maybe they did. Maybe it drew them. Maybe they thought he could rise, against ridiculous odds, once again.

He couldn't. He might have been an Angel, but he was just a man. On the 18th stage of the Giro, descending the Colle di Sampeyre in driving hail and rain, Pantani crashed. There is a photograph of him the moment after the fall, sitting on rain-slicked grass, clutching himself, crying. His fans screamed for him to continue.

Continue? Il Pirata, who perceived competitors' tactical maneuvers as grievous personal affronts, who, if he wasn't stalking a pack, was assaulting it, devouring it? Il Pirata, who had been hounded by racing authorities when he should have been honored? Now that he'd crashed out of contention in his homeland's biggest race, his fans wanted him to join the pack, to continue when he could not triumph?

Angels confound. They perform the impossible. They find the perfect gesture at the most unlikely moment. And now, Pantani did it again. He gave his fans their miracle. He got on his bike and he rode. Not for victory, not to mount one of his furious, quixotic charges. He rode when defeat was absolutely certain. Just so he could finish. Just because people were asking him to. It was perhaps his least-talked-about ascent, his most ordinary. It might have been his most heroic climb. It was his last.

"I'M ALL ALONE"

In the autumn of 2003, for reasons no one can agree on, Pantani traveled to Cuba. He went there to dry out. No, he flew to the island for a massive binge. He wanted to reconnect with a girlfriend he'd met at the beach on a previous trip. No, it was because Maradona, the great Argentinean soccer star and a good friend (and a recovering cocaine addict), invited him to the place he'd been treated for addiction.

For three days, my translator and I search for the rooming house where Pantani stayed in Havana, for hints about what happened. It is a strange trip. People avert their eyes and profess ignorance to the most innocent queries, and dark rumors mutate and fester in narrow, cramped alleyways thick with diesel fumes and the heavy scent of human waste. We are invited into tiled rooms no larger than small closets, greeted with warmth and wide smiles and strong, bitter coffee. We are told of a local doctor who has discovered the cure for cancer in the venom of giant blue scorpions; we listen to not one but two sordid and fantastic rumors of hushed-up prostitute murders. We see mounted upon doors crude representations of pierced tongues and covered eyes—both a religious caution against bearing false witness and a political reminder that sharing information here is dangerous. In Cuba, truth is a slippery, elusive commodity.

Yes, a local man we meet on the street in Havana says, after a couple mojitos, Pantani was here. He came in 1999, and 2000 and 2001. He led bike tours around the country. The children adored him. Fidel entertained him at one of his secret palaces. The cyclist knew that money meant nothing, that it could not buy happiness, and isn't that insight the very essence of living? And now, could we please give the helpful man some American dollars, "for cooking oil, for my sick mother." Yes, another local whispers in a bar, Pantani was here and he was quite possibly involved in the untimely end of a young prostitute—the one in the taxi, involving ecstasy and a botched Santeria cure, not the one where a woman was flung from a window of a famous tourist hotel.

"Certainly not," the mother of Pantani's Cuban ex-girlfriend proclaims. Her daughter was not the cyclist's girlfriend, they were merely acquaintances, and she has no idea how anyone could have thought differently. As she says this, her teenage daughter rolls her eyes at the translator and me.

On the third day, guided by rumors, a Santeria witch, some mojito-fueled guesses from locals, an old man selling rolled paper filled with roasted peanuts, a relentless translator, gossip, a vague article from an Italian daily called La Nazione, and dumb Caribbean luck, we find the boarding house where Pantani stayed.

"He wouldn't eat," says Lidia Dios Fernandez, the owner. "He was depressed. He took whatever pills he could get his hands on. He would open doors and just take pills. Blood pressure pills, for example. My blood pressure pills."

Franco Corsini, the Cesenatico restaurateur and one of Pantani's close friends, heard the Cuba rumors and tracked the cyclist to Havana. He and Michel Mengozzi flew from Italy to help their friend, bringing antidepressants obtained from Pantani's doctor back home.

Fernandez says that before Pantani left her boarding house, he gave away a $20,000 Rolex watch and his bicycle to the poor children of the city. Sebastion Urra Delgado, a Cuban hunting guide who extricated Pantani from Havana at Corsini's request, says that when he arrived in the city the cyclist was barely conscious and, if anyone gave away—or, more likely, sold—Pantani's possessions, it was Fernandez. "People looked at Marco and they saw a pot of gold passed out on the couch," he says.

Before he left Havana, Pantani scribbled in the blank pages of his passport. This is what he wrote: "My life is already over. The thing that matters in life is to feel deathI'm left all alone. No one managed to understand me. Even the cycling world and even my own family. I want tobreak this addiction. I want to finish with that world and I want to get back on the bike."

"WHO IS THAT BALD GUY?"

Back in Italy, when Pantani drove to meetings with drug dealers, Michel Mengozzi followed on his motorcycle hoping to dissuade him. He rarely succeeded.

Pantani checked into drug rehabilitation clinics twice, but lasted only days each time. At the second one, in Milan, he had cocaine smuggled in. In a published interview with Pugliese, his journalist friend, in September 2003, Pantani declared that he was done with cycling forever. Pugliese says he asked his editors if he could write another story. "Marco Pantani's going to die," he says he told his editors. "Can we help him? Can we run an article about his drug problems?" He thought a good headline would be "Silence Is Killing Pantani." His editors declined. At the beginning of February 2004, a week before his friend's death, Pugliese wrote Il Pirata's obituary. "And I could have written it six months earlier," he says.

At the end of what would be Pantani's last stay at the family villa, his mother emptied his wing. "What a thorough cleaning job you're doing," he said. She always knew when he was going to fall. She had a feeling.

On Monday, February 9, he checked into room 5-D, a split-level room on the top floor of Le Rose with a view of the Adriatic. He wanted it for only one night. "He seemed very sad," says Silvia Deluigi, the hotel owner's daughter. Una grande tristezza. "It was clear he wanted to be alone."

He made five or six phone calls, came downstairs then walked into the winter night. Two hours later, he returned. He wouldn't leave the hotel again.

Every morning, Deluigi took a brioche and coffee to Pantani, and every morning, he asked if he might have the room another day. Every night, a waitress from Oliver Laghi's restaurant showed up with a pizza.

On Saturday morning, Valentine's Day, some of the guests on the fifth floor came downstairs to complain.

"They said, 'Who is that bald guy upstairs?'" says Pietro Buccellato, the hotel clerk and a foreign affairs student at the local college. "'He's acting weird.'"

Other guests complained. Pantani was screaming. There were loud, banging noises. When Larissa Boyko, the cleaning woman at Le Rose, knocked on the door, Pantani screamed at her until she went away. Buccellato went upstairs to investigate.

"I heard furniture moving around. I talked about it with the owner and he said 'Let's say we have to change towels as an excuse.' I called, but the phone was always busy."

At 8 p.m., Buccellato went upstairs and knocked at the door to 5-D. There was no answer. At 9:30, he knocked again and, this time, opened the door with a manager's key. The lights were on, the furniture upturned. Pantani was on the top floor, next to the bed, facedown. There was swelling in his brain and lungs, brought on by an overdose of cocaine. He was 34 years old. He'd been dead for six hours.

THE MYTH

It could have been me. I didn't possess extraordinary athletic gifts, nor fame, nor money, and I was 30 pounds overweight and I lived in a cluttered, one-room apartment in a Midwestern suburb and binged on cheeseburgers and vanilla milkshakes and read detective novels until sunrise, but other than that I was exactly like one of the greatest climbers who ever lived.

At first it was just a few beers and occasional cocaine, not a lot, just a normal amount for a guy like me. And then it was more than a normal amount. I remember myself as a sweet kid, and I had a sweet tooth, too. But sometimes the mask slipped. Sometimes the monster scrabbled out. There were nosebleeds and vomiting and car wrecks and hurt feelings and lost jobs and liver disease and worried people who didn't know what to do. Bad things happened, and things got worse.

Can we learn from Pantani's end? And what is the lesson? That those who climb too fast, too far—like Icarus and all other mortals who dare to spread their wings toward bright, shining suns—must surely crash to Earth?

It's bullshit. Why can't his mother and managers and friends and fans see that? Why can't people see that? There is no cautionary tale about fame and greatness here, no lyrical saga of hubris and tragedy. I could have died like Pantani. I could have died exactly like him. There would have been nothing lyrical about it.

Of course other cyclists have taken performance-enhancing drugs. Some have been caught; others, no doubt, haven't. Maybe Pantani was singled out by a cycling establishment terrified that the savior of the Tour might be exposed as a cocaine abuser. Maybe he was hounded. But others have been singled out. Others have been hounded. It hasn't killed them.

Other cyclists have used recreational drugs, too, including, no doubt, cocaine. In 2003, the great Jan Ullrich, Armstrong's arch-rival, was temporarily banned from cycling for testing positive for ecstasy. It didn't kill him.

Italy's great cyclist, one of the greatest climbers of all time, the doomed Angel of the Mountains, died not because of judges, or lawyers, or reporters, or the cycling community, or his parents, or the embarrassment of oversized ears or an uncaring world or mysterious, shadowy overlords hatching sinister plots. He didn't die because he was hounded. He didn't die because anyone failed him.

It's cruel and narrow-minded to reduce a man's life to a medical diagnosis. Pantani brought a bruised majesty to cycling and it was a rare and precious and thrilling thing that should be acknowledged, and remembered. But we shouldn't forget the sordid way Pantani left this world. He lived as an Angel. He died as a drug addict. He died because he was a drug addict.

That I managed—with a great deal of help—to quit drinking and taking drugs makes me feel enormously, stupendously, ridiculously lucky and grateful. Why couldn't Pantani quit? Here are better questions: When will the family and friends and fans and country that loved him, and those who merely loved the idea of him, stop making up fables? How can a country be so stupefied by grief that it can't admit the truth? That its hero's demise was neither mythical nor profound, but merely stupid and sad and sick and utterly wasteful?

CERTAIN SUMMER DAYS

A woman crosses herself, kisses the medallion of the Madonna hanging from her neck, then pulls out a digital disposable camera. She snaps a shot of the flowers arrayed in front of Pantani's memorial—the lilies, gladiolus, carnations, plastic roses and daffodils, the peonies, the black-eyed Susans, the sunflowers. She wears a shapeless, dark-blue dress and her face is heavily lined. She might be 55. She might be 75. Her husband wears shorts and Nike sandals and he, too, crosses himself, then kisses the cross around his neck. A young man is with them, perhaps 20, perhaps 30, perhaps mentally disabled or palsied, and he moves with the un-self-conscious clumsiness of a very small child. His head rocks from side to side and every half-minute or so, he exclaims "Pantani! Pantani!" and gurgles.

It is late afternoon on a hot Wednesday in early July, another windless, cloudless day. For 45 minutes, couple after couple, family after family follow the path marked by signs the cemetery's management has taped to walls and posts—Marco Pantani Viale NO. 6 on heavy plastic yellow paper with arrows. There are no other signs in the cemetery. All the visitors cross themselves. Most take out digital cameras or cell phones. Some leave notes, keepsakes. One man rode his bike 150 miles here, then left his shirt, on which he wrote, "Certain summer days in Cesenatico seem to reflect the light the way a pirate lit up his people." A note pinned to a spray of plastic roses says, "Good-bye, pirate of Romaglia, with pain I mourn you like a son. I remember when we met."

"He seemed like a son," says Liliana Pessarelli, a visitor from Modena. "Last year we came to visit his house, but he wasn't there. So this year we've come to the cemetery."

"Nobody could have believed when he died," says Giovanni Minconi, from Carrara, in Tuscany. "If he would have lived, he would have been a champion again."

At his funeral, the mass of mourners stretched 2 miles, in lines six across. There were reports that 30,000 filed past his casket. Today, a typical day at the Cesenatico cemetery, a hundred people come to cross themselves and to take pictures and to telephone friends back home to tell them where they are.

"I used to work in peace," says Ennio Bazocchi, the graveyard caretaker, with a deep sigh. "Before we could leave [tools] around. Now there are just too many people."

One couple leaves the memorial, another couple arrives. More crossing, more disposable cameras, more flowers. At this very moment, no doubt, families are packing their cars in Rome and Naples and Venice, preparing for a journey to the final resting place of the funny-looking little man who achieved so much and died so horribly wrong, so horribly alone.

It is cloudless and windless, oppressively hot, and a sheen of sweat covers the faces of every single one of the mourners, or fans, or deluded pilgrims, or vultures, or whatever they are. The older couple and their son, or grandson, are still here. She weeps, her husband stares at the flowers. The boy makes his sounds.

"Pantani!" he croons, over and over, occasionally gurgling, rocking his head. Does he know whose name he sings? Does he understand why the great champion is gone? Is his dull, ragged mourning less profound than those who make a martyr of the fallen cyclist, or is this the sound of genuine sorrow, at perfect pitch?

A hot, still day, cloudless and windless, broken only by the sounds of cameras clicking and the man-child's sad, sad song.

"Pantani! Pantani!"

This article ran in the December 2004 issue of Bicycling.

Steve Friedman is a writer based in New York whose work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, Esquire, GQ, Outside, New York magazine, Bicycling, Runner’s World and many other publications.