Are we more lonely than our ancestors?

More people than ever are suffering from the ill-effects of loneliness. As BBC Radio 3’s Free Thinking Festival prepares to tackle serious questions around our fear of being alone, Professor Barbara Taylor sets out to discover whether our current loneliness epidemic is really the modern phenomenon we believe it to be.

The message is everywhere: loneliness is a “modern epidemic”.

The news reports make grim reading: nine million British people are lonely, while a third of American citizens suffer from loneliness. Many of these people are elderly individuals living on their own, but other age groups don’t escape; young people in particular are said to be plagued by loneliness.

The health consequences are dire: lonely people are said to have a 50% higher risk of dying early. For the young, loneliness is more dangerous than smoking or obesity. Across Britain, charities like Age UK and Mind are trying hard to mitigate the problem. In January 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May announced the appointment of a minister for loneliness, declaring: “For far too many people, loneliness is the sad reality of modern life.”

That loneliness is a serious issue is undeniable. But is it a distinctively modern problem? After all, aloneness - meaning physical solitude - is hardly new, and the price of such aloneness has often been high.

“The man…[whose] solitude is such that he could never see a human being… would abandon life,” the Roman statesman-philosopher Cicero declared in 44 BCE.

“Solitude,” the poet John Donne complained in 1624, after a period of quarantine during a serious illness, “is a torment which is not threatened in hell itselfe.”

A century later, Robinson Crusoe’s account of his desert island solitude impressed readers with the horrors of involuntary aloneness.

“Oh that there had been but one or two, nay, or but one soul saved out of this ship… that I might but have had one companion, one fellow-creature, to have spoken to me and to have conversed with!” – Crusoe wails to himself in Defoe’s novel, clenching his hands together so hard in his agony that for a time he cannot pull them apart.

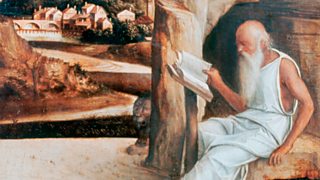

Of course solitude has always had its devotees.

Christianity in particular has sponsored many solitaries, from medieval hermits and anchorites to modern spiritual contemplatives like the writer Sara Maitland. For these people, lone religious worship is far from lonely, being filled with God’s presence.

In fact, most varieties of “solitude” in the Western tradition have been experienced as scenes of presence, not absence – whether that presence is divine, human or imaginary. Renaissance and early modern solitaries like Francesco Petrarch and Michel de Montaigne shared their “solitude” with intimate friends as well as God, muses and remembered beloveds. Jean-Jacques Rousseau shared his with his long-suffering wife and a host of fantasied lovers. Even that iconic Romantic solitary, William Wordsworth, was accompanied by his sister Dorothy when he was dazzled by dancing daffodils.

Noma Dumezweni reads Wordsworth's Daffodils

Actress Noma Dumezweni reads I wandered lonely as a cloud by Wordsworth

Pre-modern “solitude” was surprisingly social.

A life of total aloneness – “absolute solitude” as Rousseau and others dubbed it – was generally perceived as toxic, resulting in lethargy, melancholy or even madness. Only God could be completely solitary, it was said; human beings are social creatures who cannot subsist alone.

We are made for Society and Solitude is an unnatural Being to usLetter to the Spectator, 1711

“Be not solitary, be not idle,” Robert Burton counselled in his Anatomy of Melancholy in 1621, a dictum that was endlessly repeated throughout the following centuries. “We are made for Society,” a woman wrote to the Spectator magazine in 1711, “and Solitude is an unnatural Being to us.”

Thus the idea of solitude has always been problematic. Nonetheless, recent centuries have seen a marked change as “loneliness” has gradually displaced “solitude” in our vocabulary. Prior to the late 18th century, “lonely” referred mostly to places and seldom to people.

But by the beginning of the 20th century, “lonely” people were everywhere in Western society as urbanisation, community breakdown and the relentless rise of competitive individualism left many individuals feeling stranded – “lonely in a crowd”. Today we take these antisocial pressures for granted – until a crisis reminds us of their terrible price.

Are we facing a crisis of loneliness now?

I believe more people are lonelier now than ever in the past. As history shows, solitude can be a positive experience, but it can also bring great suffering. If government is serious about reducing this suffering, it has a big job on its hands.

Barbara Taylor is Professor of Humanities at Queen Mary University of London and is currently researching attitudes to solitude in Enlightenment Britain. She joins the medievalist John Henry Clare and writers Sara Maitland and Lionel Shriver at this year's Free Thinking Festival to to contemplate the many sides of solitude.

-

![]()

Free Thinking Festival: Are we afraid of being alone?

A panel of writers and academics convene to try and answer this age-old question.

-

![]()

In Our Time: The Philosophy of Solitude

Many thinkers have dealt with the subject, from Plato and Aristotle to Hannah Arendt...

-

![]()

Is loneliness affecting your health?

Claudia Hammond invites you to take part in the BBC Loneliness Experiment.

-

![]()

Free Thinking Festival 2018: The One and the Many

Browse all the events, programmes and features from this year's festival.