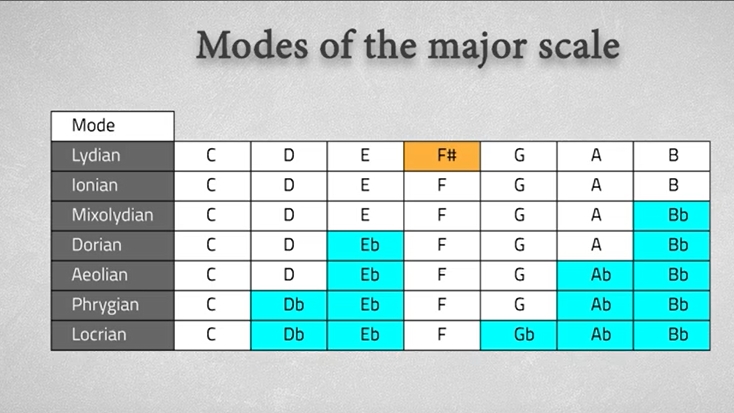

I want to tell you more about modes! I’ve been playing music and thinking about modes a lot, but now I have more to say. In Part 1, I described the 7 modes formed by starting the major scale at various points:

I linked to videos where you could hear samples of music in each of these modes. I showed how to order them from ‘bright’ to ‘dark’:

and I showed that inverting these modes maps the brighter modes to the darker ones, reversing the order of brightness, with Dorian getting mapped to itself.

In Part 2 I took a different tack, focusing on the cube of modes that can be obtained from the major scale by flatting the three ‘flavor notes’, the third, sixth and seventh:

As we move down this cube, we reach darker modes. But since this cube doesn’t show modes with a flatted second or fourth, it doesn’t include the darkest of modes!

Today I want to take yet another approach. Let’s look at all scales where we choose 7 notes from the 12 notes in the usual chromatic scale. There are

scales of this sort, which is too many for me to talk about today. So let’s impose an extra constraint! Let’s say that the biggest allowed step between consecutive notes is a whole tone. So, the only allowed steps are a whole tone (w) and a half-tone (h).

It turns out there are far fewer scales of this sort: just 21. That’s a lot less! We’ll see that they form 3 groups of 7. Seven of them come from the major scale, seven come from the minor scale, and 7 come from a less well known scaled called the Neapolitan major scale.

To see this, the first step is to notice that an octave goes up 12 half-tones, so a 7-note scale obeying our extra constraint must have 5 whole-tone steps and 2 half-tone steps. There’s no other option, ultimately because

There are lots of different ways to climb up the scale with 5 whole-tone steps and 2 half-tone steps. The white keys on the piano do it like this:

They form a scale called the ‘major scale’. The steps between the white keys go like this:

w w h w w w h

As we climb up the major scale, we go up a whole tone when there’s a black key between white keys, and a half tone when there’s no black key between white keys.

By playing a scale with 7 notes, going up the piano on white keys only but starting wherever you want, you can get these scales:

The first one here (reading across) is the major scale, and they’re all called ‘modes’ of the major scale. Each of these 7 modes of the major scale, has its own cool-sounding Greek name, and I discussed them all in Part 1:

All these 7 modes have two half-steps that are 3 whole-steps apart or 2 whole-steps apart.

But there are also 7 modes that have two half-steps that are 4 whole-steps apart or 1 whole-step apart:

These are called modes of the ‘ascending melodic minor’ scale—one of the commonly used minor scales. If the piano was designed with these modes in mind, it might look sort of like this:

And there are 7 more modes, which have two half-steps 5 whole steps apart or right next to each other:

And these, it can be shown, are all the possibilities! So, there are

scales with 7 notes, each separated by either a whole tone or a half-tone from the next.

Next time I’ll say more about these 21 scales. Many are used in multiple contexts and have several names. Here I’m trying to use some of the more commonly used names:

• Part 1: modes of the major scale.

• Part 2: minor scales, and a cube of modes.

• Part 3: all 7-note scales drawn from the 12-tone chromatic scale with at most a whole tone between consecutive notes.

• Part 4: modes of the major and melodic minor scale.

• Part 5: modes of the Neapolitan major scale.

• Part 6: the special role of the Lydian mode, and the circle of fifths.

• Part 7: cycling through all 84 modes of the major scale in all keys.

• Part 8: how the group acts on the set of all 84 modes of the major scale in all keys.

I really enjoy your music theory posts. Makes me wish I’d gotten deeper into theory back when I was playing. I haven’t played in many, many years, but these posts make me want to dig out my keyboard and put into action the things you’re talking about. Haven’t done that yet, my arthritis and severe hearing deficit have made it harder to enjoy, but maybe one of these days! These three Modes posts would make a great starting point.

Thanks! I’m going to keep talking about modes for at least a while longer. I’m sorry it’s tough for you to play the keyboard these days. Luckily you can have fun just playing a scale in these modes—no virtuosity required.

Yeah, growing old sucks. I pulled my keyboard out of the closet and plan to give these modes a try. I used to do a lot of improvisation, and it would be fun to try that in the context of these modes.

p.s. Your in-post link to part 2 links to part 1.

And, FWIW, in the WordPress Reader (that misbegotten piece of software), the characters open-parens, w, close-parens get displayed as the WordPress logo. Displays as intended on your blog website.

Thanks for catching that link mistake.

Wow, it’s annoying that (w) looks like the WordPress log on the WordPress Reader. I’m not going to do anything about that.

One of many, many annoyances. I wish there was a better blog platform for long-form bloggers, but I haven’t found one.

I decided to add a picture of a keyboard that was optimized for the ascending melodic minor scale:

[…] John Baez has been putting out an excellent series of posts about music theory on his blog. The most recent, the seventh, is about how you can generate scales by picking out piano notes in intervals of fifths. What’s interesting is that you can generate all seven major scale modes in each of the twelve […]