Critics Page

Paula Rego and Balzac: A Footnote

- Paula Rego

- Story Of The Story

- Conclusion

Some years ago, Paula Rego was invited by an editor to participate in a collective volume or exhibition of paintings after Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece (Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu), which is possibly the most written about story in western literature. This proposal excited me because I had already suggested several times to Paula that she explore the story. I became obsessed with it in the 1980s, wrote a commentary, and made the first complete translation for a hundred years.

The story is about an invented painter of genius, Frenhofer, and his obsessional perfectionism. The real-life Franz Porbus and Nicolas Poussin are the other main male characters and friends of Frenhofer, who is one of Balzac’s most significant crazies. The description of Frenhofer’s final painting announces modern art—abstraction and abstract expressionism—a premonition well understood by aficionados of the story, including Giacometti. The Chef-d’œuvre so intrigued Cézanne that he pointed to himself when Émile Bernard mentioned Frenhofer, as reported by Rilke in a letter to Clara without naming Bernard.

Such an attitude is a long way from Paula’s restless and multivalent imaginaire, which is closer to Picasso’s, although he too was fascinated by The Unknown Masterpiece, and indeed lived in the very house that the court painter Porbus inhabits in the story, 7 rue des Grands Augustins in Paris, near Pont Saint Michel.

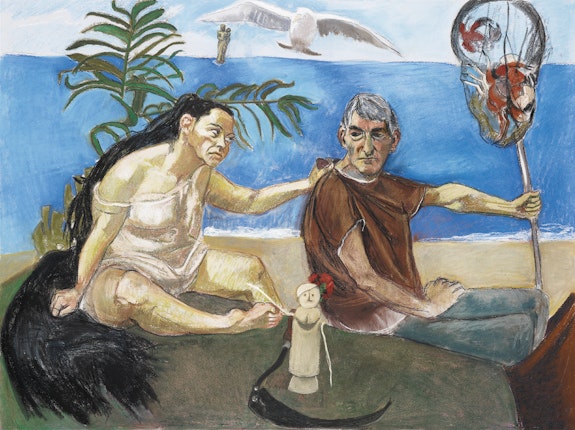

Paula turned down the editor’s invitation but something lodged because a few years later she made three pictures: The Balzac Story, Mary of Egypt, and, especially, Painting Him Out. Here I am now, writing about a painting I am in: At once a model leaning against the picture within the picture, and inside the picture within the picture, before the painter drapes a green serge cloth over the canvas, as at the end of Balzac’s story. As with her other paintings triggered by literary works, Paula makes them her own. Henceforth independent of the original, her deep concerns are refracted through a story she has read and introjected.

A collage of historical and legendary allusions, multiple mythological structures and theorizing about art, The Unknown Masterpiece is built upon many dichotomies: sex and love, poetry and painting, writing and painting, painting and life, knowledge and commerce, money and fame, myth and art, art and history—and yet, thanks to the writer’s genius, it is satisfyingly poised in its nervous tension and stable disequilibrium. The three painters are counter-balanced by three women (one real, two paintings), two saints who become whores by being exposed to the gaze (embrace, knowledge) of the second painter, and mediated by the third painter’s woman, a painting of Mary of Egypt who was both saint and whore. Love is at the heart of this story, which incorporates, incarnates, a network of myths. It embodies a dual system of exchange, a triangle of men superimposed on a triangle of women.

Poussin, like Rilke, finds it easy to let go, Frenhofer—like those whom Rilke addresses in one of his greatest poems, “Requiem for a Friend,” namely Paula Modersohn-Becker—has the opposite problem:

So the fault is this, if there is any fault:

not to increase the freedom of a loved one

with all the freedom you find within yourself:

for when we love we have nothing but this:

to let each other go, since holding on

comes easy and we do not have to learn it.

It is easy to forget when reading this story that its locus is neither the 17th nor the 20th century, but the early 19th century. Beneath the layer of Romantic ideology about the solitary artist (one of the earliest portraits of the condition), lies the prophetic sub-text embedded and embodied in the story’s deep structure: that for many artists achievement henceforth implies the central principle of anxiety/doubt/failure/incompletion/revision. Can anyone familiar with the life and work of Cézanne and Giacometti fail to identify their own readerly hindsight with Balzac’s authorial foresight or precognition, fail to read these great and exemplary artists into and out of Balzac’s story?

There is a true and beautiful Borges-like story that in one of his houses Balzac had written either on the wall or inside empty frames: “(Here),Velásquez, (here), Delacroix, (here), Raphael”—quite a parable of the writer’s felt life. One is tempted to add: “(here), Giacometti, (here), Frenhofer, (here), Modersohn-Becker, (here), Rego.” Frenhofer was one who, as Gertrude Stein said, “walked in the light and a little ahead of himself, like Raphael.” The Unknown Masterpiece is a supreme meta-fiction, a pictorial writing telling scriptural paintings. The true story about the empty frames prefigures not only Borges but also conceptual art. Paula is the opposite of a conceptual artist, so called, so it is a pleasure for her model to turn the tables, enter her into the spirit of his text, just as she painted him into the picture.

Note: This text is partly new and also draws on my Gillette or The Unknown Masterpiece (1988 reprinted in 1999).