ArtSeen

HIROSHI SUGIMOTO:

Gates of Paradise

Gates of Paradise opens with an image of one of the Hiroshi Sugimoto’s signature subjects, the open sea, captured in black-and-white. Through a foggy, grayscale haze one can make clear the ripples on the water, a horizon line in the distance. The sea fills the image to its margins, making it appear as if the water goes on forever. Mediterranean Seas, Cassis (1993) is paired in the first gallery with Leaning Tower of Pisa (2014) a striking shot of the iconic building taken dramatically from below. The two photographs together offer a succinct summary of the show’s narrative arc, which unfolds just inside.

New York

Japan SocietyOctober 20 – January 7, 2017

Portuguese travelers, their ship battered by a stormy sea, landed by accident in the Japanese archipelago in 1543. It was the first documented encounter between Japan and Western delegates, and marked a brief opening of cultural exchange between the two far-flung regions. Missionaries had introduced Christianity to Japan by 1549, and thirty-three years later, a remarkable voyage, known as the Tenshō Mission, was undertaken—four teenage Japanese boys embarked on an eight-year journey to Europe, as ambassadors from their homeland to the Continent. They toured extensively through Portugal and Italy, and were celebrated by the highest emissaries of the courts and the church of both nations throughout their travels, culminating with an audience before Pope Gregory XIII. By the time the boys returned to Japan in 1590, however, the fruitful period of dialogue was already on the wane. The practice of Christianity in Japan was soon to be restricted, then banned altogether by 1614. Non-Japanese natives were forced from the country and by 1623 the period of Isolationism had begun. It would be over 200 years before Japan experienced again anything more than minimal contact with the rest of the world. The triumphal Tenshō Mission was both a beginning and an end.

Sugimoto first learned of the Tenshō Mission while photographing the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, Italy, in 2015 as part of an ongoing project of documenting theaters. While there, he discovered a fresco panel on the wall, which depicted the boys’ visit to the building upon its inauguration in 1585. Fascinated, Sugimoto delved into their history and soon decided to trace their path through Italy, chronicling the sights they would have seen on that epoch-making journey. Interspersed throughout the exhibition of photographs are examples of nanban art—traditional Japanese works that depict or were inspired by the presence of foreigners—culled from around the period of the boys’ lives. It makes for a beautiful, though somewhat hodgepodge conceit.

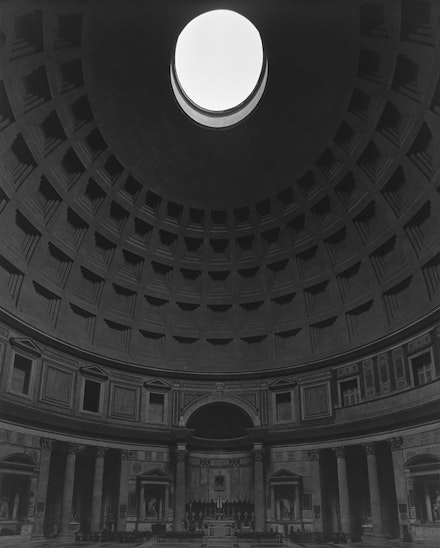

One large room is dedicated solely to Sugimoto’s photographs of architectural sights that would have been highlights of the mission’s grand tour. Most of them capture landmarks that have been so extensively photographed their depiction might border on cliché if not for the fact that Sugimoto’s clear-eyed, pristine images render them almost otherworldly. In Pantheon, Rome (2015) the artist was allowed to enter the building in the middle of the night during a full moon, to capture the architecture in a moment that it is almost never seen. Lit only by the luminous moonlight that pours through the ceiling’s oculus, and bereft of any signs of life, the crystalline image captures the building’s fine-boned architectural details and also the sensation that the viewer has stumbled into the central hub of a UFO.

This gentle push-and-pull between strangeness and the familiar pervades the exhibition, and is the thematic tenet that holds the viewer aligned with these teenage missionaries. The pulling together of Sugimoto’s very contemporary photographs along with centuries-old artifacts sometimes feels cumbersome, but luckily nearly every object on view is exquisite. A 16th century, six-paneled folding screen, Scenes of European Ways of Life, vibrantly depicts views of bucolic, Continental countryside life. The vivid inks and traditional materials root the work in classical Japanese art but the scenes—which feature components such as a distinctly temple-esque castle and sheep drawn proportionally to humans about the size of small dogs (sheep not being native to Japan)—are clearly filtered through a Japanese imagination.

The final room of the exhibition is given over to Sugimoto’s large-scale photographs of the Gates of Paradise, ten gilt-bronze panels made by Lorenzo Ghiberti between 1425 and 1452, that depict iconic scenes from the Bible and which adorn the Baptistery of St. John in Florence. His dramatic camerawork draws out the luster of the bronze panels, and the audience is treated to an opportunity to examine their delicate detail in an intimate way. This viewer’s eye was in particular drawn to the detail of a stone-laden path that bisects the scene in the panel, Joshua. In the photograph by the same name (2015), Sugimoto has apprehended the light falling on these stones in such a way that the path beckons, and becomes the central focus of the scene that is otherwise crowded with human bodies. It suggests the mortal wonderment for exploring unknown territories, for forming links across thresholds. We live in a moment where borders now exist under grotesque threat of being closed, of cultural ties being damaged and severed rather than being mended and reinforced. The impulse to connect is not new, as Sugimoto suggests, and we erode it at our peril.