When I first heard about tours that explore a township on the outskirts of Johannesburg and divulge the history of Apartheid, I was intrigued. “Sign me up!” I said enthusiastically.

And then I looked into it more.

Slum tourism, also known as poverty tourism, makes my skin crawl. The idea of turning impoverished homes into a tourist attraction reminded me of my decision to forgo the DMZ at the border of North and South Korea.

A few years ago, I spent a month travelling through India solo. I’d heard about a controversial “slum walking tour” in Delhi. But I didn’t need to go on an organized tour to see slums—they were everywhere. And, besides, the whole idea of a rich white tourist taking photos of a local’s way of life and then hopping back in an air-conditioned bus made me want to puke.

I understand the morbid fascination we have with seeing things that we know are wrong. But that doesn’t make it ethical to turn it into a tourist attraction. I live in Vancouver, and I can’t imagine an organized tour of East Hastings Street. Besides, to me, tours are the distinction between a tourist and a traveller.

But sometimes, tours are the safest—or only—way to get to know a foreign place and situation.

I began to open my mind and try to consider how touring Soweto could be beneficial, not only by giving residents the power to share their own stories, but also by bringing money into the community. And, besides, was it more “ethical” for me to sit by the pool sipping an ice-cold beer and pretend these areas and this turbulent history doesn’t exist? They do. It does. So, on my second full day in Joburg, I decided to embark on a historical and cultural tour of one of South Africa’s most prominent townships.

Lebo’s Backpackers, Soweto

We drive into Soweto from Bryanston, an upper-class suburb near modern Sandston. Already, I’m surprised by how built up Johannesburg is. One of our hosts told me “it’s first world, in third world.”

Down a dusty road, we find Lebo’s Backpackers. I love it instantly: the bamboo huts with thatched roofs, communal firepits and picnic tables beneath umbrellas painted in giraffe spots and zebra stripes. It’s the ultimate hippie hideaway.

A group of about twenty different cultures gathers behind the bohemian park. “Thank you for being here,” the main guide says as he welcomes us to the hostel’s backyard. “I didn’t grow up during Apartheid. It was bedtime stories for me. I hope to share some of these stories with you today.”

“We have a big issue with unemployment here, and by choosing to come on the walking, tuk -tuk and bicycle tours, you are giving us jobs. So, from everyone in the local community you can’t see but are helping to employ, thank you.”

He invites us to introduce ourselves and then brings us on stage to sing and dance a version of “Awimbawe.” It’s ridiculously fun and puts us all in good spirits—the best way to dissipate any tension we might’ve felt by journeying into Soweto.

We split into our groups. Four of us remain for the walking tour. We begin by trekking through the hostel’s permaculture initiative. “Food is expensive today,” Mfundo, our guide, says. “So we grow our own to use in the kitchen.”

An employee, Jonas, tells us more: “These gardens are three months old. We grow basil, spinach, mint, baby maro, eggplant… we feed the soil, and the soil feeds us.” Jonas explains that visitors can come volunteer and mentions the importance of a project like this in Soweto. “It’s living in a ghetto, but not letting the ghetto affect you.”

Mfundo leads us up the hill for a sweeping view of Soweto. In the distance, we can see the World Cup training stadium and the iconic electric generators with a 100-metre bungee jump strung between them.

Mfundo tells us that Lebo’s started as a hostel. The owner quickly realized guests needed something to do when they woke up. He began gathering bicycles from the community to rent out and eventually launched the three different tours. Today, the hostel employs about 25 people. I ask him how he feels about Soweto becoming a tourist destination.

“When the buses just come through, locals don’t like that. It’s about humanity,” he explains. “Tourists walking through and spending money in the economy is different. It’s beneficial.” Mfundo is from Soweto. He seems excited to show us around.

“41 townships make up Soweto,” Mfundo says as we wander through rows of elephant-roof houses in Orlando West. “Every township has its own name. The most spoken language is Zulu.” We learn how to say hello and respond, and practice as we pass people on the streets:

Sanibonani (pronounced: Sunny Bonanie) – Hello/I see you (plural)

Ya-bo (response) – Me too

Suddenly, we halt in front of an old women’s hostel. Mfundo talks about the atrocious living conditions in the 10 hostels throughout Soweto, back when the mines were filled with men, and families were separated for up to a year at a time.

We pass brick buildings rimmed by barbed-wire fences, government housing, children in school uniforms, churches, street barber shops and wooden stalls stocked with fruit, one of which we stop at. “Grab something,” Mfundo says. “It’s included in the price of the tour. It’s part of how we give back to the community.”

As we explore the paved neighbourhood, I find myself feeling surprised. To be completely honest, I was expecting conditions to be worse. I thought I’d feel unsafe and uncomfortable, but beneath the clear blue skies on the quiet streets, I feel… fine.

That’s not to say there aren’t worse areas—we certainly didn’t see everything. And later, I’ll catch glimpses of tin-roof houses (with satellites plopped on top) on the outskirts of Cape Town. But here, we stop for ice cream at a coffee shop, where the barista proudly boasts he makes the best coffee in the world. As I sit on the patio crunching Häagen-Dazs, I don’t feel like I’m in a slum.

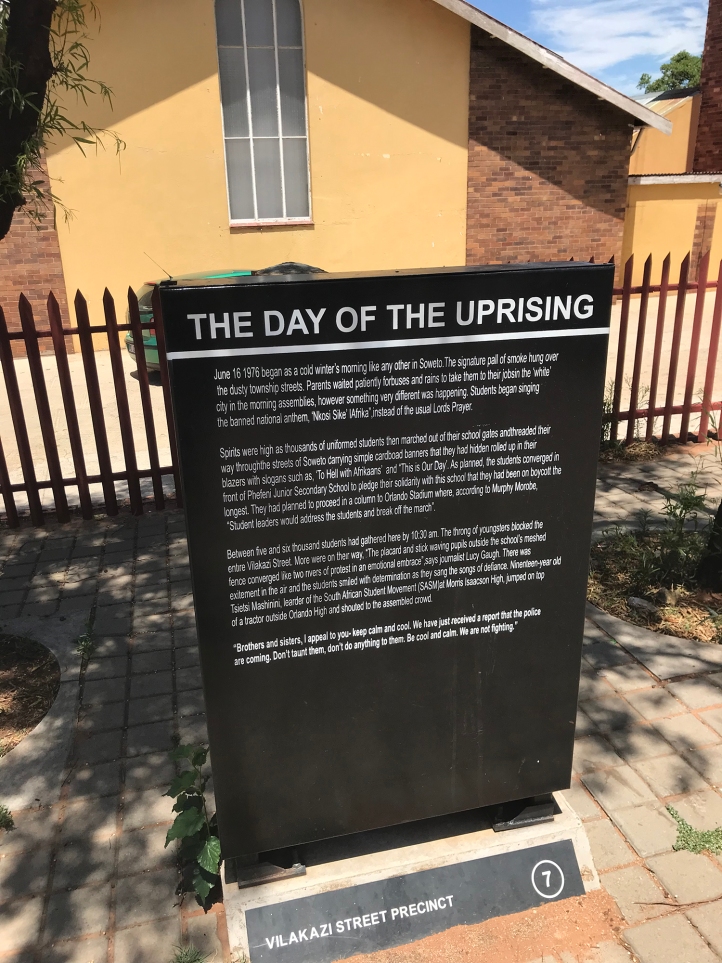

Past the Hector Pieterson Memorial and down the street to Nelson Mandela’s house, the streets become a lot busier. People sell crafts and handmade souvenirs at market stalls; groups of men perform gumboot dancing for tips. We head back to the hostel and I pester Mfundo with questions, still trying to wrap my head around everything that happened here.

At the end of the tour, we share traditional locally brewed beer and an icy fruit smoothie from clay bowls. Over the open fire, poike stew simmers in black pots: chicken, beef, vegetable and chicken feet.

We eat and drink together. It’s delicious.

Final thoughts

After exploring Soweto on foot, we visited the Apartheid Museum. We spent nearly two hours reading signs, viewing old photographs and videos and learning about what life was like during segregation, and how political prisoners fought their way out of it. It was a humbling, interesting and educational experience.

Rather than making me feel like an inauthentic tourist, the Soweto walking tour and Apartheid Museum were a refreshing break from my carefree days drinking wine. They granted deeper understanding about the complex culture of the places I explored.

Finally, I’m glad we chose the walking tour, rather than a bus tour with a large company. I felt good supporting a local hostel and walking amongst the people of Soweto rather than staring at them through glass windows in an air-conditioned tour bus. Bus tours also sometimes enter a home, which feels like a boundary that shouldn’t be crossed—and a little too much like “poverty porn” to me.

Do you disagree? Do you think I was wrong to take a tour of a township? Hey, I don’t blame you. That’s okay. We need to talk and think about and debate these ethical issues that surround travel instead of just mindlessly doing activities because they look cool.

Maybe that’s the real difference between a tourist and a traveller.

What do you think about ‘slum tourism’? Would you do a walking tour of Soweto?

I want to know! Comment below.

A very interesting article, Ali. As you know, we did not do the tour for the very reasons you mentioned, too intrusive, etc., but the walking trip seems to be quite different, connecting with the local people and not just staring at them. I am glad you found this tour, and had a meaningful experience, ( which is also what travel is about!)

Thanks so much for your input, Edna.

Thank-you for this thoughtful essay. I am planning a trip to South Africa and am struggling with how to be an ethical tourist. I am also interested in having my children learn about all aspects of South African society.

In the past (20+ years ago), I travelled and volunteered a lot. I think it was a better way to see the world but the more I read about the impact of over tourism, the more travelling becomes a challenge. (I have realized that unless things change, I may never go to Barcelona or Venice as they don’t want me there.)

I also think that that the distinction between a traveller and a tourist is not that great. There are those in each category who contribute positively and negatively. Now that I only get to go on vacations, I am firmly in the tourist camp. I have also discovered that a well done tour adds a lot to my understanding of a place.

I will consider taking this walking tour. It sounds like it was minimally intrusive and did increase your understanding of the community. It was also run by a community member which is important.

Im doing an assignment on slum tourism, I found this piece to be quite informative. Thanks

“What do you think about ‘slum tourism’? Would you do a walking tour of Soweto?”

When slum tourism is organised to benefit local people like it is in Lebo Sowetto baclpackers I thing it it is a very good thing to do.

When I am in Johannesburg I usually stay in Sowetto because it is the safest place in Johannesburg to stay.

The village justice system of local people in Sowetto makes it safe for tourists because they would kill anyone who harms a tourist and puts their tourism at risk. Not sure I agree with somebody being killed on my behalf, but it is unlikely to happen anyway because people in Sowetto would be afraid to attack me because of what might happen to them.

Ghetto Tourism is the way to go. In traveling, one of the motives is to learn and experience different cultures. The Ghetto has its own culture in Africa. It’s that culture that defines the pulse of the entire nation and its capitals. For instance, the heroes of sport, music, philanthropy, politix, business, Art etc in most African countries come from and lsome still live in the ghetto. When loaded they relocate to the low surbabia but their roots is the Ghetto and their homes, even in their absence are reverted.. So you weren’t wrong at all. Get in touch with me on my email. I have embraced that ghetto tour concept and will be introducing it in one African country (Not South Africa) in which I have interests. You cud be my next and guest. Tsar